Is it mistaken to tag Nagaland earthquake prone?

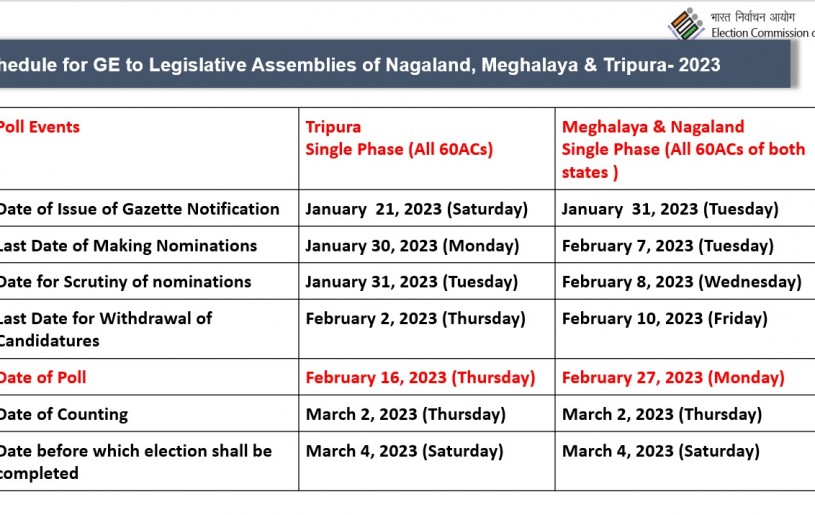

A seismic data plot of earthquakes epicentred in Nagaland recorded since 1943.

(By Dr. Watinaro Imsong courtesy the USGS Earthquake Catalogue and International Seismological Centre)

Geologists says seismic data indicate low epicentral earthquake activity

Imkong Walling

Dimapur | September 15

Nagaland state is generally regarded as a place prone to earthquakes. The north-eastern region of India, of which Nagaland is a part, according to geoscientists, is sandwiched between two tectonic subduction zones making the entire region vulnerable to seismic activity.

This is further attested by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) identifying the region as located in the most seismically active of the country’s 4 seismic zones (II, III, IV and V) or earthquake prone areas grouping the entire region (excluding Sikkim) in Zone V.

As per a report tabled by the Union Ministry of Earth Sciences in the Lok Sabha in July 2017, “Zone - V comprises entire northeastern India, parts of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, part of North Bihar and Andaman & Nicobar Islands.” It attributed the BIS for the classification of the zones.

The BIS classification together with the state’s geographical location would merit cause to give the jitters yet an observation made by a geologist speaks the contrary.

Subduction zones are those regions where the earth’s tectonic plates have collided and one plate is overriding the other. Places located over these collision zones are said to be highly susceptible to earthquakes.

Contrary to...

According to Dr Watinaro Imsong, a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Geology, Nagaland University, Nagaland has had little seismic activity as opposed to the largely held belief. Dr. Imsong based her observation on a set of earthquake data compiled by her from the United States Geological Survey Earthquake Catalogue and the International Seismological Centre. The data set, plotted on a map of Nagaland (refer plot graph), consists of recorded earthquakes epicentred within or close to the geopolitical boundary of Nagaland state from 1943 till 2019.

As per Dr Imsong’s data compilation, a majority of the earthquakes epicentred in the state since 1943 have been mostly ‘minor’ and ‘light’ in magnitude. Only 3 (highlighted in white dots) have been classified as ‘moderate’ or ranging between 5.0-5.9 in magnitude in the Richter scale.

The strongest so far, measuring 5.6 was epicentred in Phek in 2012, the second was a 5.5 magnitude in 1952 epicentred in Mon and the third measuring 5.4 was also in Mon epicentred near Tizit in 1986.

The last one epicentred in Nagaland measuring 4.2 M was recorded east-northeast of Phek in September 2018. Earthquakes epicentred in the state prior to 1943 were not considered for a lack of recorded data.

Earthquake magnitudes measuring 4-4.9 and 2-3.9 on the Richter scale are classified as light and minor, respectively. Those in the range of 1-1.9 are regarded as ‘micro’. She added that earthquakes measuring 1-3 in magnitude occur daily and rarely felt but recorded by seismographs.

Considering the existing epicentral data, she added that it is quite puzzling to note that earthquakes epicentred in Nagaland have been relatively less and far in between contrary to the ‘earthquake prone zone’ tag.

“Our neighbouring states have had one or more mega earthquakes. Assam has had big ones and Meghalaya was jolted by a major quake measuring 8.9 in 1897,” she said.

If there ever was a mega jolt prior to 1943, she maintained that there is no pre-existing seismological data to suggest there ever was one.

Research points to...

Further, if one is to account geographical distance, she held that Nagaland is geographically situated not too close to either of the Indo-Burma (east) or the Indo-Tibet (north) subduction zones. She though maintained that there is no assessment as to arrive at conclusive figures.

Taking Kohima as a reference point, the Indo-Burma subduction zone is approximated to be located at 100 -1000 km (aerial distance) and the Indo-Tibet subduction zone is anywhere from 800-3300 km.

The Assam-Tibet quake of 1950, which was actually epicentred in the Mishmi Hills in present day Arunachal Pradesh, was part of the Indo-Tibet tectonic collision, while she added that the Meghalaya quake of 1897 was an entity unto itself, not part of the Indo-Burma or Indo-Tibet subduction zones.

The biggest and the most recent quake that occurred near the Indo-Myanmar international boundary was in 1988 measuring 7.3 in magnitude, which was strongly felt in Nagaland, was attributed to “intra-plate seismicity (Gahalaut et al., 2013).”

She said, “According to recent research papers, the moderate magnitude earthquakes occurring in Nagaland or the Indo-Burma boundary are due to active lineaments/faults in the region and may cause damages to unconsolidated sediment filled valley regions. Thus, there is a need to find out which lineaments/faults are contributing to our region’s seismicity.”

Further citing Gahalaut et al., 2013 and other recent papers, she said the GPS measurements in the Indo-Burman Ranges suggest that subduction which occurred in the geological past is no longer active. “The seismic hazard in the region due to great or major inter-plate earthquake is very low in this region.”

However...

But it does not imply that one can rest assured as big earthquakes epicentred beyond the state can be destructive. She said, “We will be hit badly not because of the quake itself but due to poor town planning, poor infrastructure, poor everything.”

The vulnerability of a place also depends on the nature or composition of the soil, terrain and depth of the earthquake.

“We cannot deny we are sandwiched between two subduction zones and who knows we might get a large one.”