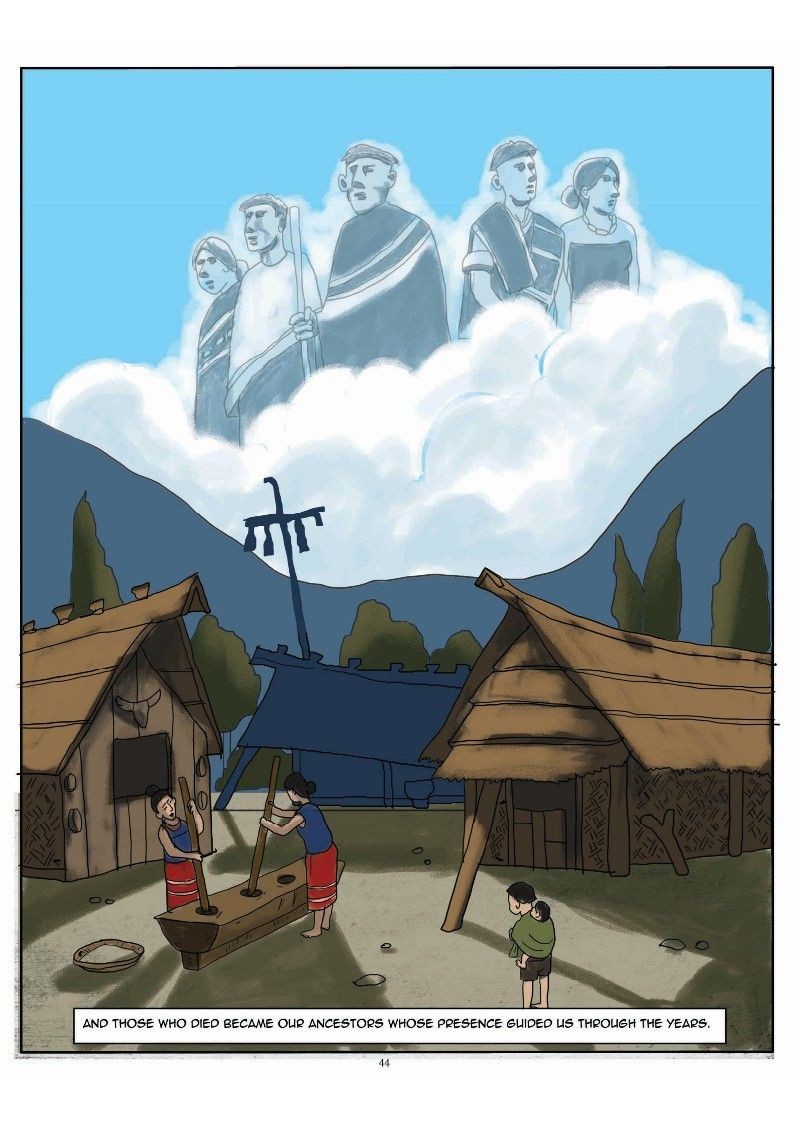

An image extracted from ‘A Path Home’ a graphic novel on Naga Repatriation by Arkotong Longkumer and Meren Imchen. The novel was released on February 17, 2023. The book is published by Recover, Restore and Decolonise (RRaD) and the North Eastern Social Research.

Vishü Rita Krocha

Kohima | March 19

During the most turbulent years of the Indo-Naga conflict, Vinyühu Meyase from Dzüleke village recalled instances of sprinkling mud or laying a hand on the dead body of a fallen comrade before continuing on their way. “With much regret, we leave them behind on the battlefield,” he expressed while relating that “in such a situation, all we could do was either lay our hands or throw dirt or leaves on the dead body as a sign of paying our last respects and be on our way.”

Meyase, who is now 91, was recruited into the Naga Army when he was 31 and spent close to a decade of his life for the Naga cause. After the dust had settled, he also witnessed people from his own community going back to the battlefield where the bodies of their loved ones lay, just to bring back their remains and give them a proper burial.

“This is because Nagas have always cared for the bodies of the dead,” he emphasized while putting across that it matters, especially for their loved ones, to bring back their remains. Sometimes, he said, “bereaved families go back looking for the remains of their loved ones even years after they are dead, and they may not even be able to identify their bodies but they bring back whatever part of the remains they are able to identify.”

In the light of the ongoing Repatriation Process of Naga Ancestral Remains, he impressed upon that it's a good initiative while reiterating that “we, Nagas, deeply care for the bodies of the dead.”

Beni Sumer Yanthan (Yanbeni) strongly feels that “the ongoing repatriation of the Naga human remains is an essential and important way of addressing and engaging with the threads of the past that we consider our 'history'.” Stating that, in a way, it is a seeking of forgiveness, she also asserted that “what we do and how we go about it will have long-lasting implications on Naga society and history.”

In the current context of decolonialism going on all over the world, she underlined that “it becomes even more important as it acknowledges and attempts to undo in some way the injustices of the colonial system, especially towards indigenous peoples.” In this regard, she further noted that “while there are advantageous processes that colonialism set into place, we must also realize that colonialism engendered a very problematic point of departure for minorities and indigenous peoples for understanding, looking, and reflecting on themselves, their cultures, and traditions.”

Pointing out that the effects in this connection can be seen even today, she also highlighted that “this is not limited only to the Naga world but also to communities in Africa, Asia, and other parts of the Commonwealth.”

‘Embrace our indigenous selves and reclaim ourselves’

Ultimately, Dr Vizovono Elizabeth, an Independent Researcher & Editor, feels that “the journey of Naga Repatriation will be a huge step towards our collective healing,” even while emphasizing that “this is an opportunity to reflect and absorb our colonial experience so that we re-learn to embrace and value our indigenous selves and reclaim ourselves.”

Stating her belief that it is opening up doors we didn’t know needed opening, she also cited two important aspects in this regard. The conversations, she observed, “are proving to be a channel of engagement and communication at a time when our society is increasingly becoming divisive.” The other point she highlighted is that “the outcome of research should not remain confined within the corridors of academia but have an impact on society, and that is precisely what this process is enabling.”

As a society, she further noted that “the Nagas have not had the time to engage meaningfully and adequately with our sense of history.” And in the process of being preoccupied with keeping up with the current events and changes in the world, she observed that “we have lost the culture of conversation.”

If you look around, she went on to state that “we are so invested in performative displays, but there are no platforms for intellectual exchange.” As a result, she pointed out that “there is very little dialogue between, among, and across generations.” There lies the danger of losing ourselves, she said while putting across, “If we don’t know where we’ve come from, how do we make sense of where we are going?”

Towards this end, she underlined, “hence it is very significant that we now have first and second-generation Naga scholars who are able to analyze, critique, and engage with our sense of history and identity.” “Undertaking this journey has directed such thinkers to engage with the communities, initiating conversations that matter to all of us,” she also added.

‘Another chance for redemption of our anthropological heritage’

Kohima-based young author, Konaei Shongdok, strongly feels that destiny has given our people yet another chance for the redemption of our anthropological heritage through the visions of Dr Arkotong and Dr Dolly Kikon, together with the unfailing support of the Forum for Naga Reconciliation (FNR) and like-minded people and organizations.

In the past several decades, he says, “the belongings and remains of our forefathers were projected as a showpiece of cultural and historical entertainment at the Pitt Rivers Museum.” However, he states with conviction that the Naga Repatriation process is headed towards a hopeful course of redemption. As the process progresses, he also cites that his mind is packed with a long list of questions. However, in this regard, he also states his belief that “we will all realize and find answers to bringing our ancestors home.”

When he first learned about the Naga Repatriation process, he took pride in the fact that “indigenous Nagas remained glued inside the pond of regional geopolitical affairs, out there the non-living represented our face to the world.”

He goes on to say that “little did my naive understanding know of all the dishonor involved in stealing and capitalizing on the prized possessions of our people by the colonials.” While some may critique and discard the thought of repatriation as only pointers of the past, he maintains that “it is the past which gave us today, and today we have for tomorrow.”

While the process of repatriation might take some years, he urges that everyone, including scholars, scientists, thinkers, leaders, artists, and tribes and people, should come together and contribute towards bringing “this long-distant ambition which can be brought home sooner or later for the healing of our Nagaland.”