Photo Courtesy: iStock

“My body is created as a three-dimensional character to dim the light of the spiritual consciousness inside me…” –Janeen

Tisha Bhavsar

Genesis

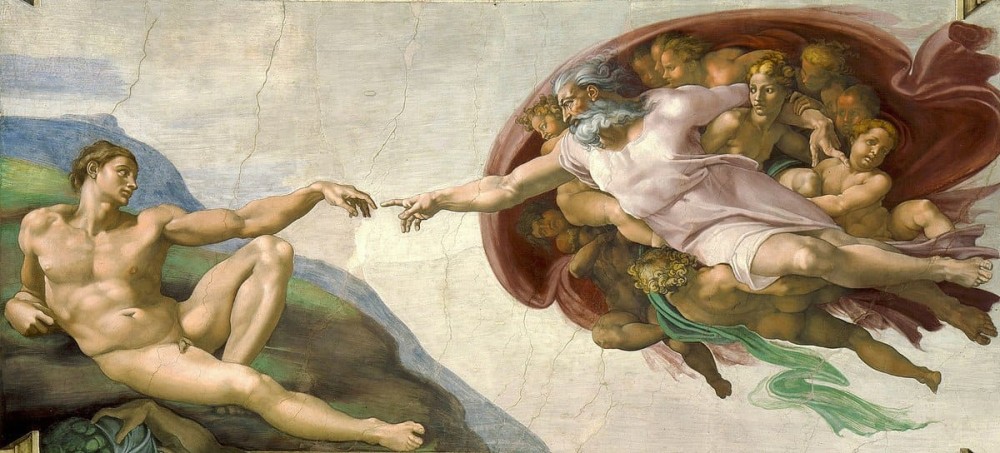

During a summer visit to the Vatican City, I found myself admiring Michelangelo's most renowned masterpiece, "The Creation of Adam," adorning the ceiling at the Sistine Chapel. This famous fresco from 1508 portrays the biblical narrative of God endowing Adam, an allegorical figure for humanity at large, with the divine gift of consciousness. Interestingly, God appears ensconced within the larger folds of an intricate structure that resembles the human brain. By igniting man’s path to intellectual development, “God” is officiating a unique marriage between the fields of neuroscience and neurophilosophy.

The painting records the moment when God is just reaching out to touch Adam's finger, kindling a spark of life and birthing consciousness. This encounter set afire several questions: What exactly is consciousness? Where does it originate? Why do we experience emotions and moments as individuals, and how do we become aware of them happening? Such was the internal tempest that inspired me to enquire further into this topic and explore one of mankind’s most significant debates: the genesis of consciousness, and where the fields of neuroscience and neurophilosophy split in their understanding of it.

David Chalmers, an Australian philosopher, and cognitive scientist, in 1995, pondered on this very question of how physical systems and bodies could give rise to subjective experiences in humans. Articulating this problem in concrete terms, he referred to it as the “Hard Problem of Consciousness”.

The Crossroads of Neuroscience and Neurophilosophy

It is hypothesised that the universe began with a sudden explosion of all known and tangible matter into existence. The first spark of universal consciousness emerged out of the void of nonexistence. “Consciousness is a kind of music that, one day, the universe began humming to itself…” (Cryptonaturalist). The ‘big bang of human consciousness’ is explained in much the same manner by neuroscience: Crick and Koch’s 1990 proposition of the ‘neural theory of consciousness’ argues for the synchronised firing of millions of neurons into mental states which went on to become consciousness. Thus exist hypotheses for neural correlations of consciousness. “Quivering glitch of a life…too ordinary to even dare remember…” (Anonymous). Individual consciousness appears emergent of the same process as the coherent existence of the larger universe itself.

On the other hand, more recent hypotheses delve into the fundamental physics of our existence, suggesting that consciousness is intricately linked to electromagnetic fields. They ponder upon the idea that our existence at the atomic level itself is defined by three fundamental elements: space, electromagnetic fields, and gravitational fields that interact with space. Their basic premise is that electromagnetic fields arranged in the form of a healthy, awake, and alert human brain create consciousness.

Conversely, within the domain of brain sciences that explore consciousness through the lens of computation, there is a belief that once we gather enough data on brain activations and connectivity, we can simulate the intricate signal processing carried out by the brain, rendering the physics of the brain inconsequential. “In brain sciences that study consciousness within the paradigm of computation, there is no perceived need to relate the model’s results to the actual physics of brains and neurons…the physics of brain cells can be entirely ignored… to accurately mimic the brain itself” (Kelly, 1994). In other words, the activities that make a brain ‘conscious’ can be created artificially by computational neuroscience without understanding what consciousness itself is.

Even philosophers have been pondering these questions for centuries. It was the metaphysics of materialists as opposed to the dualists that was further enlightening. Materialism holds that the mind is the brain and conscious mental activity is identical to neural activity. It therefore abides to some extent by neural theories which contend that consciousness must emerge from the neural functions and networks of the brain. Contrarily, dualism asserts that the conscious mind and mental states are non-physical. That is, when we reflect on our conscious perceptions, pains, and desires, they do not seem to be physical in any sense. The strong materialist-dualist conflict has given philosophy a non-uniform front in this debate.

Where The Fingers “Almost” Touch: An Explanatory Gap

All these theories, however, have failed to answer the lingering question about the origin of consciousness. Crick and Koch, the postulators of the neural theory, themselves acknowledged that while neural correlations offered merely adequate conditions for consciousness to exist, they were by no means sufficient explanations for the emergence of the phenomenon. Further, the electromagnetic fields hypothesis fails to reason why consciousness produces subjective experiences. Finally, the “computational theory”, which revolves around simulating brain signals through computer models to study the emergence of consciousness, at its core still relies on considering consciousness as a “magical” product of the brain with an unclear investigation into a deeper understanding of how it takes place.

Materialism too is challenged by Thomas Nagel's famous “Knowledge Argument” where he states that since we don’t have full knowledge about the ‘mind’ or ‘our experience as a being’, it is justifiable to infer that the missing knowledge is metaphysical and lies beyond the physicality of the body and the brain as we know it. I am of the opinion that since consciousness is rather a subjective experience, the research of some neurophilosophical theories is largely an outcome of self-introspection rather than a thorough inquiry.

In “Creation of Adam”, there exists a gap between the fingers of God and Adam. They almost touch yet never meet, those eloquent ideas of purely metric reason and flowy philosophy. Two different fields that extend explanations but a gap in their explanations eternally persists. Joseph Levine articulated this chasm as the ‘Explanatory Gap’. Why or how does some particular brain process produce that particular taste or visual sensation? It is difficult to see any real explanatory connection between specific conscious states and brain states in a way that explains just how or why the former is identical to the latter.

This 'Explanatory Gap' is essentially the aforementioned ‘hard problem of consciousness’. David Chalmers suggests a very radical idea of postulating consciousness itself as a fundamental building block of nature as one solution to this problem. He reasons it with the idea, that every time in science, we face the inability of existing physics to explain it, we declare new fundamental laws.

Parting Notes: Panpsychism

“The metaphysical dread of someone else! // The horror of another consciousness // Like a god spying on me!” – Faust

The notion that consciousness might be universal, that every living system might possess consciousness to some degree, brings us to the threshold of future research in this field. Such a view is called panpsychism which argues for ‘a mind for all’: everyone ranging from a dog to mice and flies, and even elementary particles like a photon might possess consciousness. Chalmers believes that linking this “universal” concept of consciousness to physical information processing in all systems could set us on a path to finding an answer.

To end on a hopeful note, Chalmers once remarked, “But I do think we're going to figure it out eventually. Understanding consciousness is a real key, both to understanding the universe and to understanding ourselves. It may just take the right crazy idea…!”

Tisha Bhasvar is a first-year student at Plaksha University