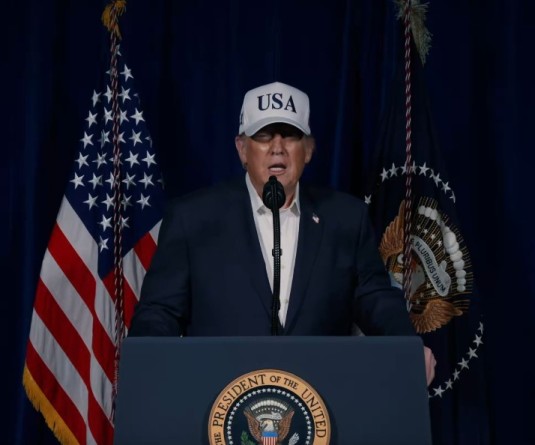

Police officers patrol a neighborhood to enforce the reimposed lockdown due to a spike in the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) cases, in Navotas, Metro Manila, Philippines on July 17, 2020. (REUTERS Photo)

MANILA, July 17 (Reuters): At the peak of the Philippines' war on drugs, people in the rundown neighbourhoods of Navotas in the capital Manila grew used to police knocking on doors, or bursting into the homes of drug suspects - who often wound up dead.

Now, many residents of the Navotas area, which has been particularly badly hit by the coronavirus, fear another harsh police campaign after the government said officials will visit homes of patients with mild or no symptoms and escort them to isolation centres.

Some Filipinos have labelled the plan "Tokhang 2", calling it the sequel to a police-led anti-drug campaign that became synonymous with thousands of killings.

"We are afraid of the house-to-house. We don't know what the police and soldiers will do to us," said Crisanto dela Cruz, a 46-year-old pedicab driver in Navotas.

"At the same time, we are afraid of getting infected because we are always outside."

Infections have tripled in the Philippines since June 1 and the interior ministry announced this week that health officials, with the help of local authorities and the police, will move people suffering from COVID-19 from their homes to isolation centres. It has urged neighbours to report potential cases of infected people who are evading authorities.

President Rodrigo Duterte's spokesman, Harry Roque, stressed the home visits will be led by local health workers.

In a statement, he said "police presence is merely to provide support or assistance in the transport of patients".

But Roque also said anyone likely to spread the virus could be forcibly removed "if need be".

"We can still compel them but I don't think it will be in the nature as if they are being treated as criminals", he told CNN Philippines.

The United Nations has said at least 8,663 people, and possibly many more, were killed in the Philippines after Duterte launched a war on drugs in 2016. It said the killings took place amid "near impunity" for police and incitement to violence by top officials.

Most of the deaths were in poor, run-down areas like those in Navotas.

Police say their actions in the anti-drug campaign have been lawful and that deaths occurred in shootouts with dealers resisting arrest.

The coronavirus strategy was announced in a week when the Philippines recorded Southeast Asia's biggest daily jump in deaths from the disease.

While much of East Asia appears to have COVID-19 under control, the Philippines has recorded nearly 36% of its infections and 23% of its 1,660 deaths in the past two weeks. In the region, only Indonesia's death toll is climbing faster.

'FASCIST ACTIONS'

The government has defended the house-to-house approach, saying that infected people with insufficient space to quarantine themselves at home should be moved to isolation centres.

But opposition senators and human rights groups say the campaign is from the playbook of the drug war.

Senator Franklin Drilon said police had been enforcing a lockdown aggressively, and there was no need for "fascist actions to demand submission".

The National Union of People's Lawyers called it "another tool to sow fear in our communities".

"With a government that has emboldened its own uniformed personnel to violate human rights with impunity, how can we be sure that the police will not abuse this new power," it said.

A better approach, say critics, is to improve contact-tracing and testing, with just 0.9% of the population tested so far. Roughly two-thirds of the tests followed the relaxation of restrictions on June 1 to try to rescue the economy.

Navotas has since seen cases grow from 286 at end May to 906 as of July 16, prompting authorities to reimpose restrictions, with armed police in camouflage deployed to keep people indoors and threaten violators with fines.

"It's not martial law, there's no need for police to go house-to-house," said Arvin Provito, a Navotas tricycle driver.

"What they should do is do house-to-house testing."

Former health minister Esperanza Cabral said the government should rethink its approach.

"As they say, give a carpenter a hammer and all he will see are nails," she said. "As for the people, they've been so used to being treated as nails they're naturally scared of anyone who has a hammer."