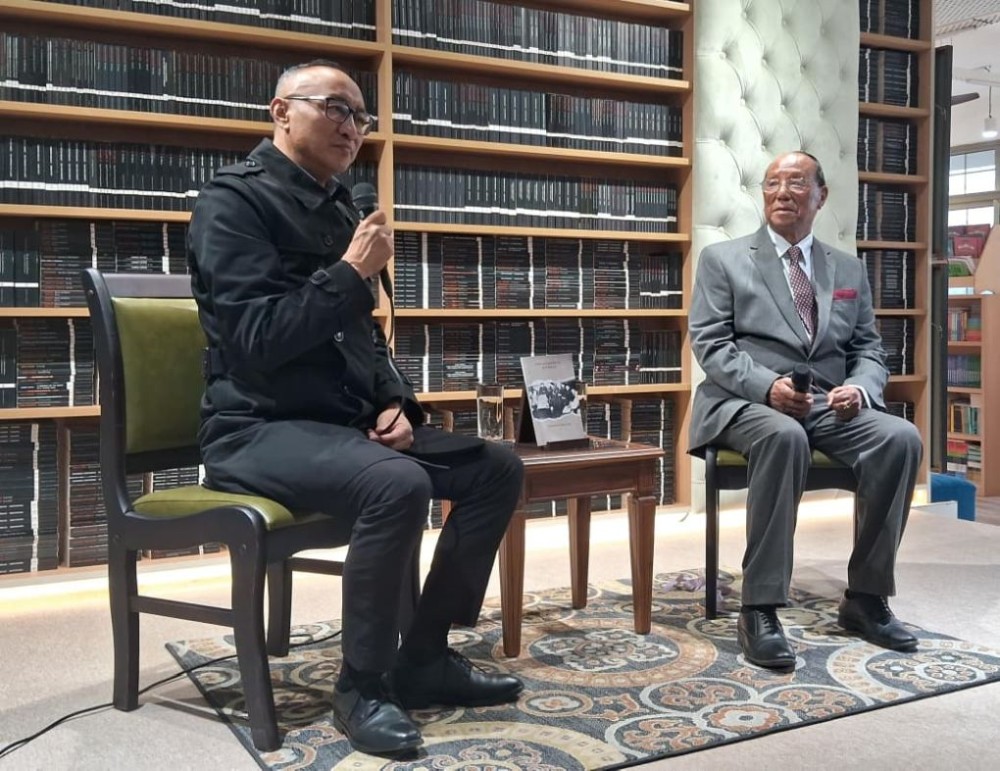

Seven-time MLA and a two-time Member of Lok Sabha, Chingwang Konyak at the launch of his book, ‘The Naga Political Movement’ in Chümoukedima on January 12. (Left) Mmhonlumo Kikon, a former legislator leading the discussion during the event. (Morung Photo)

• Says integration is a distant dream

• Statehood a necessary intervention

• Links FNT demand to funding gaps

Morung Express News

Dimapur | January 12

Chingwang Konyak, a seven-time MLA, two-time Member of the Lok Sabha, from Nagaland, and President Emeritus of the Naga People’s Front, released his new book titled ‘The Naga Political Movement’ during a launch event in Chümoukedima, on January 12. Published by Silk Route Papers, the book provides a historical account of the Naga struggle. This was Konyak’s second published work, following the release of his autobiography in November 2024.

The launch featured a discussion between the author and moderator Mmhonlumo Kikon, a former legislator and also a published author.

In the discussion, Konyak addressed the origins of the Naga identity and the internal divisions that have shaped Naga politics, and the north-eastern region of India at large, over the past century.

Konyak argued that the collective “Naga” identity was an administrative development that followed British contact after the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826. He noted that the Naga National Council (NNC), at its inception in 1946, initially sought autonomy within the province of Assam rather than total independence.

According to Konyak, the subsequent transition toward armed struggle created a permanent ideological rift between “moderates and extremists.” Reflecting on this period, Konyak said, “The seeds of divisions within the Nagas were started right from the NNC... between moderate and extremist groups.”

The discussion identified the 1947 Nine-Point Agreement, also known as the Akbar Hydari Agreement, as the primary catalyst for the splintering of the movement. Konyak explained that the then-NNC President T Aliba Imti interpreted the agreement’s 10-year special provision as a period to decide on administrative arrangements within the Indian union. However, AZ Phizo viewed the Agreement as a countdown to sovereignty. According to him, the ideological split eventually led to the assassination of moderate leader T Sakhrie and the rise of a more confrontational approach.

Konyak also highlighted what he described as a lack of political differentiation by early Naga leaders regarding the Indian government. He noted that while a delegation met Mahatma Gandhi in July 1947, they did not meet Jawaharlal Nehru, who held the actual executive power in the Interim Government. “Mahatma Gandhi is the Father of Nation but he was outside the government,” Konyak remarked. He added that decisions ultimately rest on people, who run the government, “But our people (Naga leaders of the time) did not differentiate that.”

On the issue of Nagaland’s statehood, he recalled that the Naga People’s Convention (NPC) was formed in 1957 as a measured move to stop the burning of villages and military operations. He termed the 16-Point Agreement as a necessary intervention dictated by the needs of the time, to ensure the survival of the Naga people.

Turning to current issues, Konyak attributed the ‘Frontier Nagaland Territory’ (FNT) demand by the Eastern Nagaland People’s Organisation (ENPO) to developmental lag in the area, or districts, home to the Konyak, Yimkhiung, Phom, Chang, Sangtam, Khiamniungan, Tikhir and eastern Sumi. Initially, these were covered under Tuensang district before new districts were carved out of it.

At the time of statehood, Tuensang district was accorded special provisions with the government creating a ‘Tuensang Affairs’ department headed by a legislator from the district as Minister. While the Tuensang district had a 10-year “Special Provision,” Konyak said that it lacked an independent budget, leaving it reliant on the state government's discretion.

Moving on to the contested question of sovereignty, integration, and the territorial transition of Naga territories into Indian administration, he held that it would be incorrect to claim that the Government of India occupied Naga territories. He argued that India inherited the Naga territories from the British rather than acquiring them through occupation.

As far as the integration, or consolidating Naga-inhabited areas, is concerned, he said that reorganising four existing states in the present scheme of things would be a political improbability. “Integration is a distant dream. Let's not talk about sovereignty… whether people may agree or not, but it will be a futile exercise, wasting our time,” Konyak said.

While describing the book as a record of developments in the Naga political trajectory, he asserted that the people should know the factual sequence of historical events.