Natalie Bursztyn, University of Montana

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why don’t rocks burn? – Luke, age 4, New Market, New Hampshire

While many rocks don’t burn, some of them do. It depends on what the rocks are made of – and that’s related to how they were formed.

There are three main rock types: igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic. These rocks are made of minerals that all have different characteristics. Some will melt into magma or lava – super-hot, liquid rock – when they are exposed to heat. Others will catch fire.

Rocks that burn when they get heated up are combusting. This means that elements within the rocks are reacting with oxygen in the air to produce heat and light, in the form of flames.

The elements sulfur, carbon and hydrogen easily react with oxygen. Rocks that contain these elements are combustible. Without these elements inside them, rocks that are exposed to enough heat will melt instead of catching fire.

How rocks form

Igneous rocks are formed when magma underground or lava from a volcano cools and crystallizes into solid material. These rocks are mostly made of silicate minerals that crystallize at temperatures from 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (700 degrees Celsius) up to as high as 2,400 F (1,300 C).

Igneous rocks contain few or no combustible elements. And it’s very hard to remelt them back into magma because they crystallize at such high temperatures – it would take the kind of high-tech incinerator that cities use to burn waste to make that happen.

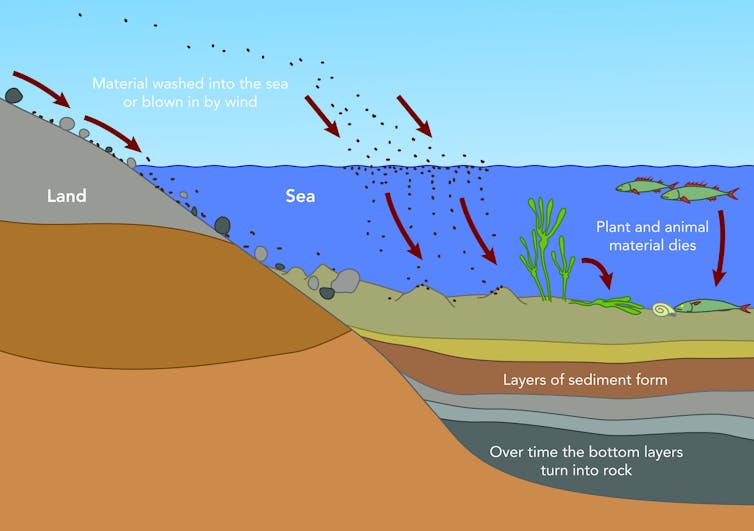

Sedimentary rocks have a very different formation story. They form from broken bits of rocks, minerals, sometimes plant or animal material, and also crystals left behind when water evaporates, like the limescale that forms in teakettles and bathtubs.

There is a lot of sulfur, carbon and hydrogen in living things. In fact, these are three of the six essential elements of life on Earth. Bits of organic matter, particularly dead plants, also are combustible and allow the rocks to burn.

The last group of rocks is called metamorphic, because these rocks form when a lot of heat and pressure change existing rocks into new types without melting or burning them. “Metamorphosis” comes from ancient Greek and means “transformation.” For example, marble that you might see in kitchen counters or statues came from limestone that was transformed under intense heat and pressure deep underground.

The rock that humans burn: Coal

Metamorphic rocks that are formed from igneous rocks won’t contain the combustible elements – the ones that burn – but metamorphic rocks made from sedimentary rocks might. One familiar example is anthracite coal, which is made almost entirely of carbon. It formed when dead plants fell into swamps long, long ago, were buried by sand or mud, and eventually were compressed over hundreds of millions of years into coal.

There are many coal seams around the world. Sometimes the coal even catches fire while it’s still in the ground. The cause can be natural, such as a lightning strike, or human activities like mining.

In Centralia, Pennsylvania, a former mining town, a coal seam has been burning for over 50 years. There are other active coal seam fires in places around the world including Zimbabwe in Africa and Jharia in India.

If carbon is compressed with even more pressure than it takes to make coal, eventually you get diamonds – the hardest mineral found in nature. In 1772, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier proved that diamonds could combust when he burned one with a magnifying glass.

With enough patience, you could burn a diamond in a candle flame. But since diamonds are quite expensive, it’s better to stick to burning other things made of carbon, like leaves under a magnifying glass, or sticks and marshmallows in a campfire, instead.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Natalie Bursztyn, Lecturer in Geosciences, University of Montana

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.