Book Review by

Shanchothung Tsanglao, Shillong

“I am awake

I am asleep

I am being shown visions.

I am seeing dreams... I see what their eyes see.”

And in that hallucinating experience in “A Bird Dreamt that it Flew”, Lhutu Keyho gives us a gist that he is a reservoir of stories and we only have to pry open; that he is always listening, always observing, always experiencing and recording lives that more than often go unnoticed. But he does not condescend. He does not tell us how to feel about these stories even. Rather, with a little kindness, he allows us to come to terms with them ourselves.

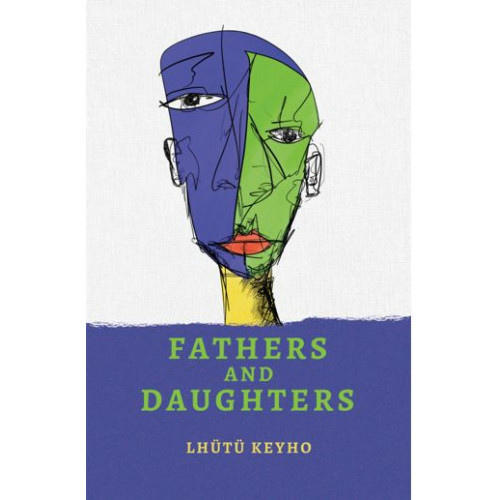

Having read his stories, which to my best knowledge began with “The Labour Unionist” published in The Morung Express years ago to this collection Fathers and Daughters, I am relieved with the assurance that he is just beginning his journey into becoming the storyteller who will tell our stories which perhaps no one else will.

In our tete-a-tetes that sometimes spiral into flying birds and Contessa bottles, always fortunately without gnashing of teeth and breaking of bones, he effortlessly morphs into a raconteur who has always something interesting up his sleeves. And just as he takes command over such sessions, his stories here will keep you on your toes. Sometimes familiar, never predictable, you are always grappling with this giant and you always emerge out with a faint smile, a heartbreak or a cathartic closure.

From the unspoken affection between a father and a daughter to the familiar constrained relationships between sons and fathers owing to one’s inability to openly communicate with each other, he tugs at your heartstrings with familiar familial ties of our own; from sparring with spirits of the old to delicately understanding the passions of a young girl and her locks, he reminds you of the stories that we no longer tell; from the innocence of youth and life in boarding schools for many, to the impending fear of punishment that reminds you of Dostoevsky, we realise his depth of understanding human emotions. And for the rest, you only have to read the book!

In “The Art of Earning Your Locks”, when the shiha asks to witness an episode of a head shaving of a young girl, I am reminded of Christoph Von Furer-Haimendorf’s The Naked Nagas who addresses the anthropological colonial centric documentation of the Nagas, “What would we think if a foreign visitor were to take out his notebook after drinking a cup of tea...and finally inquire into our customary behaviour when our wives committed adultery?”

While Lhutu Keyho sardonically ascribes the shiha with many “virtuous entities” that would please any overbearing sahib even to this day, little does he realise that by telling these stories he has become “the peace-maker, the recorder of experiences [and] the protector of the hillmen”.

For someone who buys books and usually shelve them until kingdom come, the moment I picked up Fathers and Daughters, it was as if I was in another session with Keyho and all I had to do was to let his words flow. Albeit unfamiliar with the settings of most of the stories, I was in Phek, I was seated on a black and yellow taxi at BOC, Kohima, I was in my old hostel with the little pickles I sometimes received from home, I was in a watering hole with the stench of fermenting rice, I felt the zooming cars of VIPs, I felt the age old conflicts with my own father growing up; and, for a moment, it felt like I was home again.