A Naga elder who was part of the delegation that visited the Pitt Rivers Museum in June 2025 to advance the repatriation talks. (Photo Courtesy: Pitt Rivers Museum Media)

“It is a Human Right, and it is spiritual also for the bones of our forefathers to be brought back. Their bones are not supposed to be in the museums… It has to be buried.”

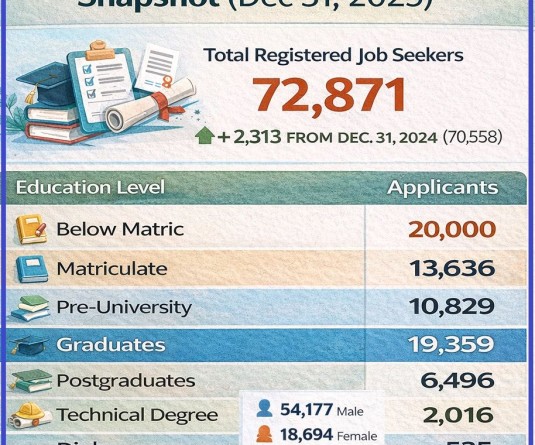

Morung Express News

Dimapur | January 6

The Naga process of repatriating the ancestral human remains from institutions like the Pitt Rivers Museum (PMR), University of Oxford is emerging as a deep spiritual and unifying journey.

Community leaders, scholars and others describe the repatriation of human remains, taken during the colonial era, as a process of telling our own stories and histories through a Naga perspective. This is not merely as a process of historical correction but as a sacred mission to heal intergenerational trauma, reclaim their narrative from centuries of literature focused on prejudice, stereotypes, conflict and forge a common identity beyond a legacy of division.

A spiritual journey to tell our own stories together

For Naga anthropologist Dolly Kikon, the journey of bringing ancestral human remains home from museums abroad is a spiritual transformation. Kikon, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, describes repatriation as a sacred experience, a sentiment fuelling a growing awareness among the Naga people.

“It has deeply, deeply transformed my life,” said Kikon who is also a member of the Recover, Restore and Decolonise (RRaD) team formed by the Forum for Naga Reconciliation (FNR) to facilitate the repatriating process.

.webp)

“I have come to realise that repatriation is a spiritual journey. It is truly a spiritual journey… we have to approach it from a place of sacredness.”

The repatriation process, Kikon said, acts as “a door into a different Naga universe,” allowing Nagas to tell their own stories. “Have a different set of eyes to look at our past and have a heart that calls for unity and that calls for fellowship,” she told The Morung Express during the September Dialogue 2025 held here in Dimapur, Nagaland.

This shift is crucial, she argues, against centuries of external focus on conflict. “The literature on Naga violence, on disunity and how we are hostile to one another has been written for centuries.

Libraries are filled with that,” Kikon said. “Starting today, if we spent our lifetimes writing about Nagas, about the small things we do for one another, how we love, and how fellowship endures despite differences and shortcomings, I think it will take more than a lifetime,” she articulated.

“Repatriation is a chance for us to rewrite our history together,” said Kikon. She asserted, that it is an opportunity to ensure the Naga future, whether in the library, in practice, or in any interaction, is grounded in love and respect, and that ‘we always treat each other with dignity.’

‘A Human Right’

For Wabang Longchari, Lead Pastor of The Lighthouse Church in Dimapur, the spiritual dimension is paramount. He grounds it in scripture, from the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib to the emphasis on proper burial in the Bible.

“It is very important, it is a Human Right, and it is spiritual also for the bones of our forefathers to be brought back,” Longchari said. The Lighthouse Church collaborates with FNR in organising the annual September Dialogue, seeing the work as a “channel of blessing.”

For Naga elders involved in the process, the mission is an emotional one. N T Thamlong Phom, vice president of Phom Peoples’ Council, was part of a delegation that visited the Pitt Rivers Museum in June 2025 to advance the repatriation talks.

“Repatriation for me is a historical and emotional journey,” Thamlong said. He believes the remains of those taken “without our consent” over a century ago have not found peace. “I feel that their soul and spirit is still wandering without the final resting place.”

.webp)

He sees repatriation as a path to collective “closure or healing” for the Naga people. “And through this healing, we can have more unity and pursue our goal together as one family.”

The idea of healing intergenerational trauma is central for many. Joel Rodrigues, a PhD scholar in anthropology, has researched the colonial context in which Naga remains were taken, often for now-debunked racial science or as war trophies.

“It started when collecting human bones was a ‘mid-Victorian madness,’” Rodrigues said. He described one case of an 18-year-old Naga servant whose skull was processed and sent to London by his British officer after the youth died.

Rodrigues also connects the historical trauma to contemporary state violence, like the 2021 Oting massacre, and sees repatriation as a potential space for broader healing. “I believe the repatriation process can address intergenerational trauma and extend care to our brothers and sisters,” he said.

Rewriting history

For younger scholars, repatriation is key to reclaiming agency over the history. Jane Seldou from Manipur said it is about giving ancestors “the most dignified respect, which was long due.”

“We can reclaim the narratives and rewrite our own history by us,” Seldou said. “We have been for a long time reading the history or the narratives which has been written by others… I think this will go on in history, which will not be biased, but very, very true to ourselves.”

Kheming Shiu, a student at the Oriental Theological Seminary, Bade called the process “a meaningful process of healing and restoring the dignity of the Naga,” which acknowledges the “wounds of colonisation.”

Naga repatriation is to “give rights to Naga people, to own the history or the memory of the past,” said Shiu and added, “By bringing the ancestral remains or the object, it not only addresses the historical discrimination, but it also addresses the social and cultural and political resilience of the Naga people.”

Nitharika Saikia, a PhD scholar from Assam, noted that Northeast India is often marked by division. She noted that to see people coming together, through the repatriation process, talking about and striving for oneness, is ‘really a big step’ for Northeast India, a region we so often see fragmented.

“This repatriation process, it is bringing all of the people together from one particular community, and I think that is a huge step,” she said.

Roderick Wijunamai, a Naga PhD student at Cornell University, New York reflected that repatriation is a space to reflect on “our past, to reconnect with our ancestors.” It is “an opportunity for going beyond our tribal lines, for going beyond our differences and fragmented space that we are in right now,” he added.

As the complex logistical, diplomatic and formal effort continues, those driving the process emphasise it is a lasting, living process. “It is an ongoing process,” Kikon said. “And it is very difficult to put it in words.”

However, its ultimate goal, as voiced by pastor Longchari, is simple and solemn, to ensure the ancestors’ bones are no longer museum exhibits, but are granted the sacred rest they were denied. “Their bones are not supposed to be in the museums… It has to be buried.”