The Unfinished Business of Poetry

By Beni Sumer Yanthan

Monalisa Changkija’s latest collection of verse, This Silence is an ode to life lived in its fullness. In many ways, the poems in this collection bear witness to the author’s life as a fearless journalist speaking unapologetically during a time when male-dominated and male-centric norms and patriarchal structures shaped Naga society. It is this characteristic vein of her personality that finds expression in her poems which weave together themes of love, aging, death, identity, passage of time, memory and solitude - culminating in a resonant and emotionally charged offering to the reader.

As someone who turns to poetry for solace, I found some of Changkija’s poems to have a profound and lingering impact - particularly those such as Shrouds of Silence, Unfinished Business, By Mistake, Tell Me Lies, and Vernal Showers which lay bare the tumult and vulnerability of love that casts shadows on the inner self, exposing emotions charged with grief, longing and unspoken desires. In Tell Me Lies Changkija writes - “Oh yes, tell memore lies/ they keep me wary/ of the duplicity of the human heart/ in the chicanery of the world”. Similarly, in Unfinished Business, she ruminates, “And I wish you goodnight too..

Hoping you will understand/ and concede someday/ why you and I will be upset with each other” capturing the ache of unresolved emotions that often place undue strain on human relationships.

On the other hand, poems such as Age-Related & Age-Defying, Is It Time Already? and At My Age reflect the poet’s ongoing preoccupation with aging. This thematic concern can be traced back to her writings from the late 1990s, a period when she was likely navigating the realities of middle age. Her poem Sunset is indicative of this where she writes, “My inspiration level is not what it used to be/ .. I forgive and endeavour to forget/ the years that rolled by/ trying to be a woman of substance”. Perhaps this is the way Changkija allows her emotions to effervesce – by quietly reckoning with time, memory and the burdens of becoming. While the temper of these poems constitutes the majority of her verse in this new collection, lines from Born to Question and You said, I replied evoke and confront the socio-political realities of Nagaland. During her 2024 speech at the A Kevichusa Citizenship Award Ceremony, Changkija paid homage through her verse wherein she awakens through poetry – a remembrance of Chalie Kevichusa, mirroring the sentiment in her poem as, “People die, you know”, you said/ “Yes, I know, but only if we forget they lived”/ I replied”. Here, we see how the poet demonstrates her ability to move seamlessly between the personal and the political, using poetry as a way to honour memory, resist erasure, reclaim the narrative and bear witness.

Changkija’s verse offers as much food for thought as her Editorials, Post-Eds, Op-eds and Anxchors. It is both provocative and insightful for the reader of today, inviting deep reflection on so many issues permeating both the social and individual fabric of our society. Yet it may be what resides between the lines of these poems that stay with the reader long after the poems have been savoured: a woman giving voice to her emotions as she moves through the rhythms of her daily life, choosing poetry as her language of reckoning and reflection. In as much as there is stillness and silence, there is also the sound and the fury.

Beni is Assistant Professor of English at the Centre for Naga Tribal Language Studies,

Nagaland University

A Silence that Speaks

By Avinuo Kire

‘For what is a poem but a hazardous attempt at self-understanding- it is the deepest part of autobiography’

This quote from Pulitzer Prize winning Poet, Robert Penn Warren, comes to mind while reading Monalisa Changkija’s third and latest collection of poetry, compellingly titled This Silence. The poems, varied in theme, fluid and evocative in her signature free verse style reads like the memoir of a woman looking back, contemplating her life. This woman is bold, unfiltered and unapologetic. Profound.

The anthology opens with ‘In My Mind’, a melancholic poem on grief and loss, on living with the pain of missing someone dear. The final stanza expresses frustration as well as acceptance, in coming to terms with loss.

In my mind, I’m constantly conversing with you

about my relationships with my mother,

mother-in-law and daughter,

my fears and phobias, my joys and laughter,

my anxieties about my sagging body,

thinning hair, tiny wrinkles around my eyes,

and my graying mind,

about my success with alcohol,

defeat with cigarettes, my impatience

and my inability to cry out loud

and call you.

Poems that follow, such as ‘Illusion/ Reality’, ‘Confession’, ‘Moments of Truth’, amongst others, continue to explore the many layered complexities of grief with raw honesty and an open vulnerability. ‘When I Weep’ does away with keeping up appearances and poignantly embraces grief with the verses;

I am done with facades,

my lips hurt from decades

of keeping them stiff.

I am done with definitions,

descriptions, images and adulations

of the hyped, the hyperboled

‘strong woman’ ~

inevitably perceived as high-strung and hyper-sensitive

Now I will be human

and weep when it hurts,

A bit of brokenness is necessary to create art. And so, brokenness here finds its release in poetry, as attested through these lines from the poem ‘Because’;

It is because I’m lost

I can find my poetry and music within me

to guide me to where

I can be found.

‘Vernal Showers’ is a particular favorite, emotively weaving verses on finding healing in nature, in springtime showers;

These vernal showers

that lash against

my window panes

or pour gently

on my roof top

cleansing and renewing

my entire being

But grief is a relentless companion, stubbornly persisting. In the same poem, the poet masterfully navigates joy alongside heartache with the following lines;

These days

I take

what I can

giving what

I have

knowing these

vernal showers

gently pouring outside

no longer hold

dreams of passion

or promises

for one steriled,

and exiled

by advancing years

……….

What a shame

these vernal showers

cannot wash away the stains

nor put out the fires.

As with Grief, Youth and Age are also recurring themes, beautifully juxtaposed with poems like ‘Sunset’, ‘Marks of Time’, ‘Age Related’ & ‘Age Defying’ and ‘At my Age’. ‘They say’ is a lovely little poem which instills courage to just be, to speak up and not be confined or restricted by societal norms.

Must I know how to sing, to sing?, the poet challenges.

For students of literature, Changkija’s writings are often associated, if not synonymous, with themes pertaining to gender, protest/resistance, and culture. In this regard, the poet does not disappoint with ‘Take this Name’ a thought-provoking poem which takes on the Ao Naga custom which stipulates that only the name of a married woman may be returned after her death, if she was married into another village. The poet urges that her name to be taken now, on her own volition, and asks;

Why wait for death to take

what must anyway be returned?

Themes on mortality and death pervade throughout the collection with powerful poems like ‘When I die’, ‘The Hours say’, ‘Is it Time Already?’ and ‘When I Died’. Changjika has the ability to treat seemingly grave themes with a lightness which is familiar, while still deep and contemplative. Skillfully employing sparse language, the two-line poem ‘You said, I

replied’ elucidates how there are greater fears than physical death.

“People die, you know”, you said

“Yes, I know. But only if we forget they lived”, I replied.

At times, the reader might feel like he or she is in intimate conversation with the Poet, other times, there is a quality of listening into a private conversation or an inner monologue. That many of the poems are dated lends a touching intimacy to the entire collection and forges a familiarity between the poet and reader.

‘Don’t bank on me’ is written with refreshing directness as evidenced by these candid excerpts from the poem

I really don’t know what tomorrow would bring

I’m only a journalist, and a human to boot

Not a soothsayer.

…...

And who am I to challenge

the tenets of democracy,

and the role of the Fourth Estate

I vowed to uphold, on my own volition,

which wasn’t anyone’s bone of contention,

when I made my decision.

Be all that as they may,

go ahead, and do your thing.

I just want you to know

Don’t bank on me.

…..

I’ve never been a good shoulder to cry on,

I’ve never pretended otherwise.

And I’m not about to change my ways.

Poems like ‘Moments of Truth’, ‘Empowerment’, ‘Irrelevant’, ‘Master Suckers’ and ‘Miasma’ continue in the same autobiographical vein which is resilient and uncompromising, with a touch of irreverence. ‘Unfinished Business’ is delightfully unabashed with its acceptance of an unfinished business between two friends which might always remain unfinished.

The title poem ‘This Silence’ and ‘Conversation with Silence’ personifies silence in a way that is discomfiting while deeply heartfelt.

The poem ‘Music in the bathroom’, effectively ties the spirit of the entire collection- which is indisputably indomitable. The poet writes;

I resolved ~ from today I quit

cigarettes, all toxicities ~ people and non-people,

exercise, lose weight, stuff myself with fruits and veggies,

generally do what Doctors say I must.

And all this I resolved after lighting another cigarette,

while pouring myself a Brandy

~ what’s a girl to do when it’s a dark cloudy day, freezing?

And our Power Department decides to take a break,

maybe it’s worked for the best ~

I discovered I am a great bathroom singer

I could sing all the notes, you know.

With 2020 starting with a freezing water bath.

I think the message is clear

~ I must now consider a career in music in the bathroom.

In light of the range and nature of themes, this specific choice of poem seems intentional and movingly symbolic. The struggles and aches remain, and yet, in the new year, the poet chooses to shift focus on music in the bathroom. This is Monalisa Changkija

Dr. Avinuo Kire is a noted poet and author

A Review of This Silence

By Tilottoma Misra

There are some women who appear to the world as strong, courageous and bold, but who occasionally bare the secret sufferings of their souls through poetry.

Because poetry is the medium through which a poet may act as the “unacknowledged” legislator of mankind, it can also provide the path of escape to souls immersed in pain.

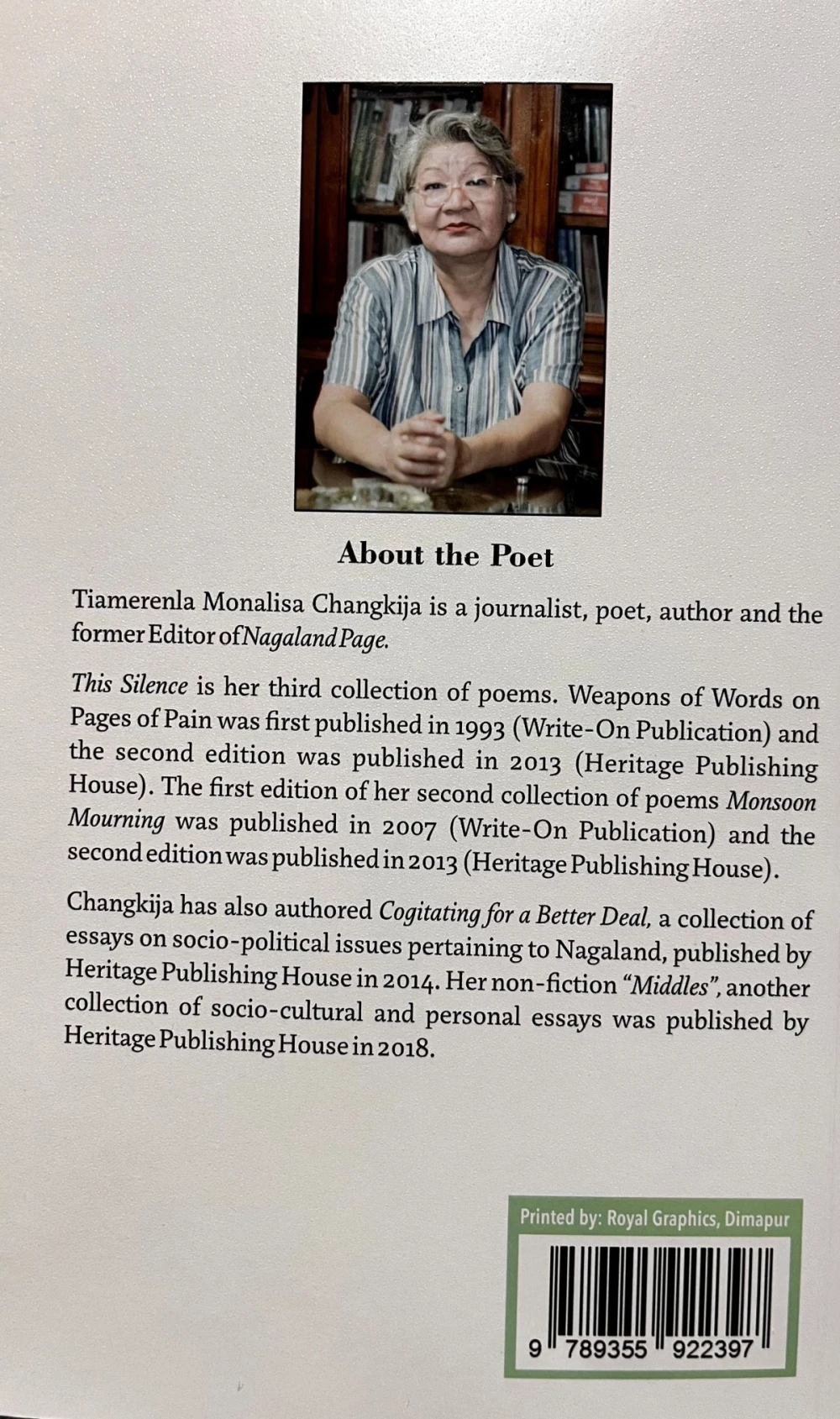

Monalisa Changkija is known to the world as someone who upholds the civil rights of the indigenous people of her community not only through her journalistic writings but also through participation in long-drawn litigations to restore constitutional rights of the people. She has also been the most outspoken spokesperson for gender rights at home and outside. In one of her earliest publications, a book of verses called “Weapons of Words on Pages of Pain” (1993) Monalisa has reflected deeply on domestic violence which exists in most societies including that of the Nagas, and asserts that the problem is personal as well as political for her. Against the weapons of violence which the patriarchal society wields in order to silence women, she triumphantly holds up her weapons of words which have the power to sensitize the society about an inhuman system where men assume the role of God: “If God made man/in his own image,/where shall the battered seek Justice?” In her rich array of journalistic pieces and middle-liners too, Monalisa boldly comments on the political and social problems confronting the Naga society which has just crossed the threshold of a new millennium.

On a personal note, I have been reading Monalisa’s poems eagerly for more than a decade and a half now. To be more specific, I chanced upon her poems at the time when I was collecting pieces of writing from the North-eastern region of the country for an anthology which was published by the Oxford University Press in 2011. I was immediately captivated by her forceful, yet sensitive, expression of concern for the wounds inflicted by insensitive people on nature as well as human beings and her bold protest against the gun-culture which has been destroying the lives of people of the Northeastern region. In some of her poems collected in “Monsoon Mourning”, I have discovered qualities which can move the readers to reflect deeply on life, death and the mysteries of nature. These poems also hold out hopes for a better future for humanity:

One of these decades when our dreams

Become as real as the nightmare now

We will gather around the fire

On moonlit nights as did our forefathers

And silence the gunfire with our songs…

When such a woman bares her secret sufferings through poetry, one is awestruck by these unseen dimensions to her personality. The poems which find a place in the present volume seem to be resurrecting some thoughts which had been pushed to the secret chambers of the poet’s heart during her tumultuous career as a successful journalist and social rights activist. These poems are genuine songs springing from a suffering heart: as she abandons all facades and cries out in

“When I weep”:

I am done with facades,

my lips hurt from decades

of keeping them stiff.

I am done with definitions,

descriptions, images and adulations

of the hyped, the hyperboled

‘strong woman’ ~

inevitably perceived as high-strung and hyper-sensitive

Now I will be human

and weep when it hurts,

smile otherwise

and confess all fears,

frustrations and failures

that come with the living,

the aging and the diseased.

Now I will heed to

the human me

and revel in

solitude’s offerings.

The reader will at once discover another kind of boldness in this volume called ‘This Silence’. In the poet’s silent communion with her heart, she redefines the meaning of concepts like ‘empowerment’ and ‘liberation’ which are used so casually in everyday parlance or in public speech: “If my personal, private, professional and public life/must adapt and suit to yours/I am a long way from empowerment”, says the poet . Such realizations are a sign of maturity for a writer and the sensitive reader can only celebrate this necessary transition in her career.

Dr. Tilottoma Misra is an author and former Professor of English, Dibrugarh University