Panel discussion on ‘Trendspotting: The Virtue Trap—The Immoral Ways We Teach Morality’ held The White Owl Literature Festival and Book Fair.

.jpg)

Morung Express News

Chümoukedima| February 19

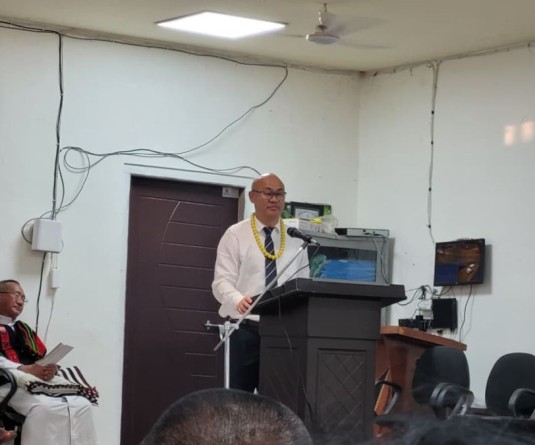

At the second edition of The White Owl Literature Festival and Book Fair, a thought-provoking panel discussion titled “Trendspotting: The Virtue Trap—The Immoral Ways We Teach Morality” brought together four distinguished panellists and a moderator to examine the complexities of morality, its construction in childhood, and its evolving nature in contemporary society.

The panel featured Dr Brainerd Prince, Director of the Centre for Thinking, Language, and Communication at Plaksha University; Rhea Kuthoore, an educator and researcher in childhood studies; Geetika Timmins, founder of Anyuna Bija; and Molona Wati Longchar, a creative professional and independent consultant. The discussion explored the shaping of morality in children and the interplay of media, education, and cultural influences.

Geetika Timmins highlighted the profound impact of media on children, stating that today's youth are increasingly shaped by digital exposure. “Whether it’s positive or negative depends on parenting and education,” she noted, using Coldplay’s Chris Martin as an example of an artist who represents authentic goodness, contrasting it with the performative morality often seen in celebrity culture. The challenge, she explained, is distinguishing between genuine virtue and the mere appearance of morality in an era of social media projection.

Rhea Kuthoore approached morality from a philosophical perspective, advocating for the recognition of childhood as a vital space for ethical formation. “What is the ethics of childhood? If we centre children’s voices, we shift morality from a rigid framework to an ongoing negotiation of power and choices,” she argued. She emphasised that morality should not be an aspiration for perfection but rather a continuous process of engaging with life’s complexities.

Dr Brainerd Prince traced the historical evolution of childhood, pointing out that it is a modern construct. He argued that in earlier times, children were treated as small adults, learning trades and responsibilities from a young age. “We must be cautious about boxing children into the category of childhood. It can sometimes disempower them by limiting their access to the complexities of the adult world,” he said, while adding that a more integrated approach to moral development was needed.

As a writer for children, Molona Wati Longchar spoke about the balance between simplification and complexity in storytelling. “Morality involves cultural nuances and biases, making it essential to provide children with an anchor, like a North Star, to help them navigate ethical dilemmas,” she noted. She also highlighted the influence of religious texts in shaping morality, particularly in Nagaland, where the Bible is deeply ingrained in cultural identity.

Dr Prince further expanded on the philosophical roots of morality, contrasting Western traditions with Indian concepts. “In the West, morality is often seen as a set of rules—what is permissible and what is forbidden. But in Indian philosophy, the equivalent of morality is ‘dharma,’ which is more fluid and contextual. Morality, therefore remains an evolving discourse tied to culture, tradition, and societal expectations,” he explained.

The discussion recognised that morality is not static but an ongoing negotiation shaped by personal experiences, societal structures, and philosophical traditions. As the panellists highlighted, whether through education, media, or literature, the way “we impart morality to children must remain a topic of reflection and discourse in an ever-changing world.”