Published by Tajung Publications, Nagaland 2025

Review by Dr Kevileno Sakhrie

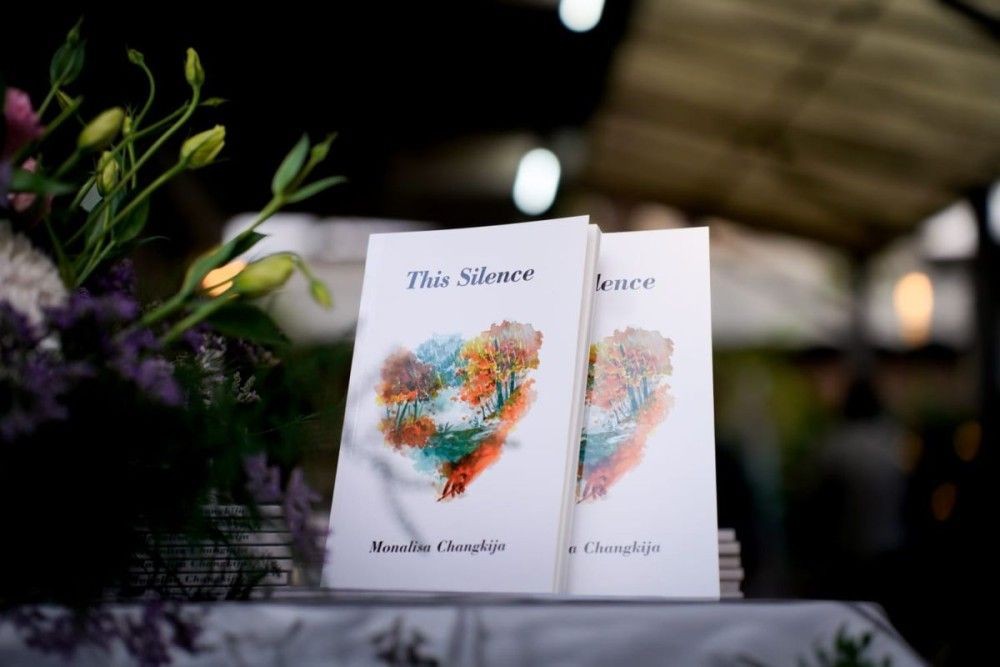

This Silence (2025) is a recently released collection of poems by renowned Naga poet Monalisa Changkija, one of the pioneers of Naga literature in English. In this respect, her greatest impact as a poet has been her contribution to the reconstruction of the Naga female ideology that is denied in real life. In prompting hard questions about the place and relevance of feminist ideas in Naga society, her poetry has been instrumental in providing a new lens into the intersections of gender, race, sexuality and ethnicity in Naga indigenous contexts. Her latest offering This Silence is a revelatory piece of work, one that includes several hitherto unpublished poems as well as some previously published in other anthologies and journals. The poems are loosely organised on the basis of composition date written across a span of three decades. Both in form and substance, they reveal an evolutionary aspect of Changkija’s poetic self and provide a fascinating impression of an artist in the process of discovering and unlocking her true power.

Throughout the collection, Changkija combines the intensity of confessional poetry with directness and lyricism. Her neo-confessional speaker quietly opens up to allow the reader to see her very bones moving, as it were. The reader is pulled into an intimate, enclosed space that is both comforting and suffocating. Changkija’s images of these spaces - homes, bedrooms, the lover’s embrace, shrouds, the grave, the body — recur throughout the poems. These can be spaces of comfort and containment, insulated from the external world (‘immuring comfort zones’) but they also have a dual nature in that they can also become suffocating, constricting and restrictive. And it is in these spaces, that identity is either recovered or lost.

This volume is in many ways unlike her earlier works that are often critical, hard-hitting commentaries on Naga society, particularly on the oppressed status of its women, although here too, feminist undertones and overtones underpin the entire collection. What is different about the poems under consideration is that they are highly personal compositions representing different phases in the poet’s own life — plain statements of art that reveal her private experiences. Fictionalising herself in order to create a retrospective truth about her life, Changkija utilises her recollected memories not only to explore her lost self, but also to employ such reminiscences to recreate a modified self. It could thus be safe to say that the primary concern of this work is self-definition or a redefinition through meditations on the loss of love, on life after love and on love after love.

Special mention must be made of the poem entitled Vernal Showers, a long ten-part poem which, in some ways, can be said to set the theme and tone for the entire collection. Well-known for her conscious use of nature and ecology as a means for asserting identity, Changkija imbues these stanzas with haunting lyricism placing the reader in a pastoral landscape of ‘verdant hills’ and ‘vernal showers’ brilliantly conceptualised in the book’s cover. Clearly identifying herself with these renewing and life giving waters, she reveals how nature and woman are synonymous. One could say that her assertion of the female body as life-source and representation of nature’s dynamic properties shatters the self-proclaimed power and superiority of the male over the female body. The poem obviously invites critical readings on the lines of ecofeminism that would analyse the interconnections between nature and women and the position of men in such a correlation. Another notable feature is how her poems repeat lines, sounds and images as they progress through the stanzas forcing the reader to re-conceptualise each poem again and again. This is an uncanny experience as the lines are familiar and yet unfamiliar; the same words and sounds are seen again in a different space in which they acquire new meaning that sometimes obliterate the old. And in these lines that mirror and distort each other, that echo and negate each other simultaneously, Changkija distils the frustrations of her own mind and grapple with the claustrophobic spaces in which conceptions, identity, truth and reality are as close as they are far away.

Running through the poems is the theme of estrangement, of couples drifting apart, of separation and leaving. This we infer from the author’s use of marital/divorce metaphors that indicate parting and collapse— “going/go” “leaving behind”, “packing”, “farewell note” and so on. Poetry that broods over the negative side of marriage or on the estrangement of unhappy couples is not new. Nevertheless, Changkija aims at contemplating much more than just that. Estrangement, even ‘divorce’ could also signify the separation of man or woman from his or her self, or of the artist from society, of the private from the public or even of the disintegration of old cultural structures. Such separation displays itself in the breakdown of natural love ties and bonds, in fractured identities or relationships. All culminate in the isolation of the individual, in loss of dreams and ideals, even of whole value systems. As such, the poems can be read as studies on the damaging effects of past history and memories, of diminished dreams, and the detrimental aspects of aging, time and death. Painfully frank, the poet turns inward to examine what her fragmented self has suffered. Poems such as "Mirrors of Perfect Purity" or "Marks of Time” demonstrate to devastating effect, how such an estrangement can be reflected, fragmented and distorted through continual mirror tricks. In this respect, her fierce endeavour to reconstruct her wounded identity and to ascertain her wholeness is all the more poignant:

I am done with facades

……….

I am done with definitions ..

Although each piece is listed and numbered as a separate poem, they are definably linked. Often laced with irony with an eye for the absurd in modern life, her poetic voice is incisive, self-mocking at times and without any self-pity whatsoever. The poet walks through darkness searching for an answer to the silence after heartbreak, simultaneously refusing and attempting to mend herself on these pages. Her memories become conversations: the self is portrayed as trapped in a world that speaks incessantly to this trapped self. This tension between the active and passive aspects of the self is a mark of the woman writer’s struggle for self- definition and differentiates her efforts at self-creation from those of her male counterparts. When Changkija declares, “in knowledge lies freedom” she is acknowledging that this drive to self-knowledge for women is more than a search for identity: it is a part of their refusal to engage with the self-destructiveness of male-dominated society. Hence, her struggle to emerge from a painful and anxious confinement into the open spaces of her own authority is understandably underscored:

I will be what I must be

my very own woman.

Through the intimate and vulnerable free verse, loosely lyrical style that Changkija employs, the reader is invited to reflect on the breach between the ideal and the reality and to experience the alienation, isolation and loneliness of the speaker. The dry humour and focus on the mundane seems an attempt to fill in the silence, to hold back the onslaught of self-reflection that can accompany grief. And so, those brief, poignant moments of lightness and levity—as if to provide some sense of relief in between moments of existential dread—start to make sense. Given the provocative nature of the collection’s title, perhaps a nuanced account of the decisions of silence made by Changkija would be crucial to understanding its role in her work. Silence is ambiguous and can be read as a revelatory and transformative space, especially for women writers in the wake of their close proximity to silence throughout history. By combining the idea of silence with words, this author is able to produce a meaning and expression that would otherwise be left unspoken as the poem The Strong One (so reminiscent of Sylvia Plath’s The Courage of Shutting up) shows. She also embarks upon a writing strategy whereby silence is used as a language to break free from the textual restrictions of Standard English and to create an appropriate medium for the expression of the female self. We may read the utilisation of the omission of superfluous words (ellipsis), punctuations and hyphens, her employment of caesurae and blank spaces of silence as an attempt to imbue her writings with meaning and emotion that cannot otherwise be expressed. Coincidentally too, one of the poems is actually called Blank Spaces (much before Taylor Swift ever thought of it). A methodology of reading the silences in Changkija could be a useful tool to recover and re-interpret her work.

The author shows how language has trapped women as well as liberated them. Feminine language is the language of contradiction, fluidity, and illogicality, non-rationality and so on. It goes without saying that Monalisa Changkija possesses these characteristics of feminine language. Suffice it also to say that it is part of her attempt to deconstruct male control by deliberately undermining the hierarchical orders of male rationalist philosophy by breaking from the ideal of coherent meaning and rational style. She emphatically asserts the right to write, so much so that she uses the expression “I write" several times in the collection. "I write”. emphasises the connection between the first-person narrative and the act of women’s speech, between the expression of her feelings and thoughts and the legitimate professional exercise of that expression. The right to write is closely connected with every choice that women might wish to make.

Through the first person voice of this major poet from Nagaland, This Silence ironically breaks a very specific silence. Changkija becomes the speaker-poet speaking for women, of all that has been hitherto repressed and forbidden within a complex social web that has always been (and is still) dictated by a dominant male culture. By situating herself as an identifiable and convincing ‘subject’ of her own art, she displays a deep level of self-awareness and control over her own narrative. In doing so, she powerfully defines her creativity and ability to speak patriarchal discourse with utmost boldness and passion. Truthful and courageous, This Silence offers its readers a haunting insight into the resilience of a woman’s spirit that keeps going even when the world offers no applause.

*Note to the reader: A word of caution may be needed for readers who might confuse confessional poetry or autobiographical literature as dealing with literal facts in the author’s personal life. It must be stated that such writing can have a fictional foundation or could blend reality with imagination. “Confessional” poetry does not necessarily always mean a confession and poetic truth is not necessarily always autobiographical. The poet may change facts, even invent some: it is an artistic method of recapturing, selecting and reshaping real experiences with which readers could identify.