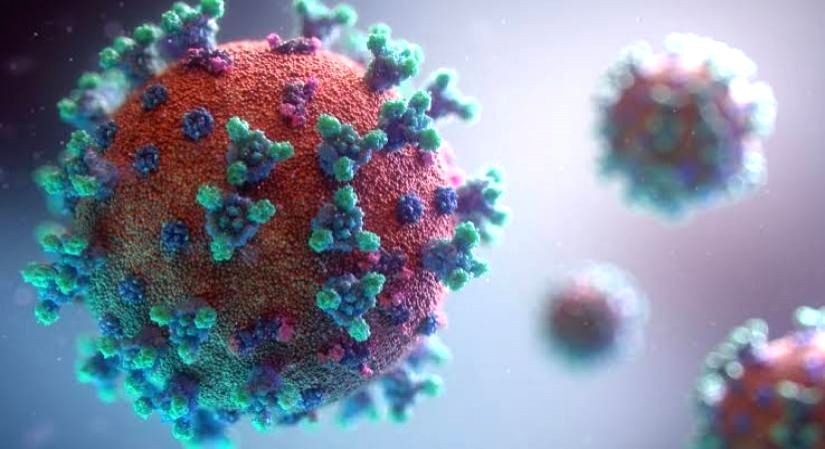

IANS File Photo

Boston, March 18 (PTI): Coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, may be vulnerable to ultrasound vibrations, within the frequencies used in medical diagnostic imaging, according to a study that used computer simulations.

The researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US modelled the mechanical response of the coronaviruses to vibrations across a range of ultrasound frequencies.

They found that vibrations between 25 and 100 megahertz triggered the virus' shell and spikes to collapse and start to rupture within a fraction of a millisecond.

The finding, published in the Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, shows this effect in simulations of the virus in both air and in water.

The team said that its findings are a first hint at a possible ultrasound-based treatment for coronaviruses, including the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

"We've proven that under ultrasound excitation the coronavirus shell and spikes will vibrate, and the amplitude of that vibration will be very large, producing strains that could break certain parts of the virus, doing visible damage to the outer shell and possibly invisible damage to the RNA inside," said Tomasz Wierzbicki, professor of applied mechanics at MIT.

"The hope is that our paper will initiate a discussion across various disciplines," Wierzbicki said.

The researchers noted that the preliminary results are based on limited data regarding the virus' physical properties.

They said that it remains to be investigated how exactly ultrasound could be administered, and how effective it would be in damaging the virus within the complexity of the human body.

In their study, the researchers introduced acoustic vibrations into the simulations and observed how the vibrations rippled through the coronavirus' structure across a range of ultrasound frequencies.

They started with vibrations of 100 megahertz, or 100 million cycles per second, which they estimated would be the shell's natural vibrating frequency, based on what's known of the virus' physical properties.

When the researchers exposed the virus to 100 MHz ultrasound excitations, the virus' natural vibrations were initially undetectable.

However, within a fraction of a millisecond the external vibrations, resonating with the frequency of the virus' natural oscillations, caused the shell and spikes to buckle inward, similar to a ball that dimples as it bounces off the ground.

As the researchers increased the amplitude, or intensity, of the vibrations, the shell could fracture -- an acoustic phenomenon known as resonance that also explains how opera singers can crack a wineglass if they sing at just the right pitch and volume.

At lower frequencies of 25 MHz and 50 MHz, the virus buckled and fractured even faster, both in simulated environments of air, and of water that is similar in density to fluids in the body, they said.

"These frequencies and intensities are within the range that is safely used for medical imaging," Wierzbicki added.