Only four out of State’s 17 districts completely free of the 1958 Act

Morung Express News

Dimapur | March 30

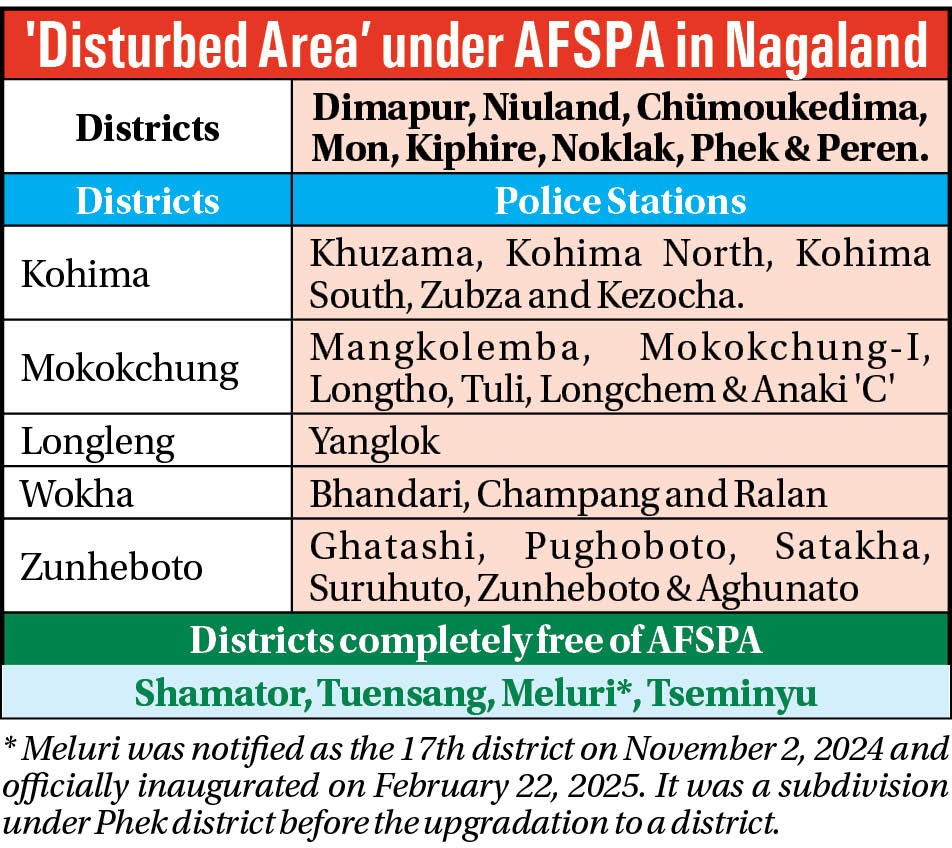

The ‘disturbed area’ tag under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), 1958, has been extended for eight districts of Nagaland, as well as 21 police stations in five other districts.

These areas are “declared as 'disturbed area' under Section 3 of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958, for a period of six months with effect from 01.04.2025, unless withdrawn earlier,” stated a notification issued by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) on March 30.

The districts are Dimapur, Niuland, Chümoukedima, Mon, Kiphire, Noklak, Phek, and Peren.

Meanwhile, out of the 21 police stations whose jurisdictions were declared as ‘disturbed,’ six are in Mokokchung district namely Mangkolemba, Mokokchung-I, Longtho, Tuli, Longchem, and Anaki 'C.'

Likewise, six police station jurisdictions are in Zunheboto district —Ghatashi, Pughoboto, Satakha, Suruhuto, Zunheboto, and Aghunato.

There are five are in Kohima district—Khuzama, Kohima North, Kohima South, Zubza, and Kezocha police stations.

In Wokha district, the areas under Bhandari, Champang, and Ralan police stations are declared ‘disturbed.’

Finally, Yanglok police station in Longleng district is on the list, bringing the total to 21.

These areas were declared as ‘disturbed area’ after a further review of the law and order situation in Nagaland, the notification added.

Accordingly, only four out of Nagaland’s 17 districts are currently ‘completely free’ of the ‘Disturbed Area’ designation under AFSPA. These are Meluri, Shamator, Tuensang, and Tseminyu.

However, the status of Meluri is unclear as it was notified as the 17th district on November 2, 2024, and officially inaugurated on February 22, 2025. Until then, it was a subdivision under Phek district and shares an international border with Myanmar.

Section 3 provisions

As per Section 3 of AFSPA, 1958, if any part or the whole of a State or Union Territory is deemed to be in a “disturbed or dangerous condition” requiring the use of armed forces in aid of civil power, the concerned Governor of a State, Administrator of a Union Territory, or the Central Government can declare the “whole or such part” a “disturbed area” by notification in the Official Gazette.

Via judicial interventions, however, a ‘disturbed area’ declaration under Section 3 cannot be issued without any time limit, and there should be a “periodic review of the declaration before the expiry of six months,” as ruled during the Naga People’s Movement for Human Rights Vs Union of India (AIR 1998 SC 431).

Besides, while the Governor is empowered to declare any area of the State as a ‘disturbed area,’ it should not be “arbitrary on the ground of absence of legislative guidelines” (Inderjit Barua v. State of Assam).

As a result, an extension or withdrawal notification of AFSPA is issued periodically.

Special powers and protection

Two of the most contentious aspects of AFSPA are the sweeping powers and immunity it confers on the “armed forces” operating under the Act.

Under the Act, the “armed forces” are defined as “the military forces and the air forces operating as land forces, and includes other armed forces of the Union so operating.”

Among others, as per Section 4 of the Act, any commissioned officer, warrant officer, non-commissioned officer, or any other person of equivalent rank in the armed forces may “fire upon or otherwise use force, even to the causing of death, against any person who is acting in contravention of any law or order for the time being in force in the disturbed area...”

The only condition is that the person acting under the Act must hold that it is “necessary so to do for the maintenance of public order” and give “due warning.”

It also provides for the power to “arrest, without warrant, any person who has committed a cognizable offence or against whom a reasonable suspicion exists that he has committed or is about to commit a cognizable offence and may use such force as may be necessary to effect the arrest.”

Finally, the Act allows the concerned person to “enter and search without warrant any premises to make any such arrest as aforesaid or to recover any person believed to be wrongfully restrained or confined or any property reasonably suspected to be stolen property or any arms, ammunition or explosive substances believed to be unlawfully kept in such premises, and may for that purpose use such force as may be necessary.”

However, legal intervention has held that “conferment of power on non-commissioned officers like a Havaldar cannot be said to be bad and unjustified,” while the armed forces “must act in cooperation with the district administration and not as an independent body.”

Section 5 provides that any person arrested and taken into custody under the Act should be handed over to the officer in charge of the nearest police station with the least possible delay, together with a report of the circumstances occasioning the arrest.

Meanwhile, AFSPA, 1958, provides special protection to persons acting under the Act. Section 6 of the Act states:

“Protection to persons acting under Act – No prosecution, suit or other legal proceeding shall be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government, against any person in respect of anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by this Act.”

Due to such special provisions, AFSPA is often criticised as a draconian law. Many incidents, such as the Wuzu and Oting killings, have failed to reach the court of law due to the lack of prosecution sanctions from the Central Government.