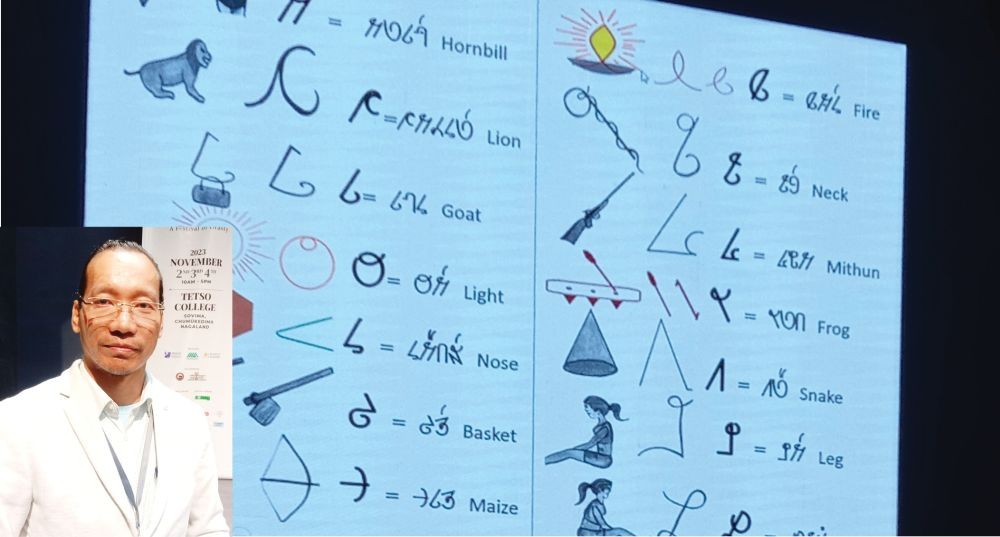

Banwang Losu at the ‘Listener Nagaland Sessions’ at the Tetso College, Chümoukedima, on November 3. (Morung Photo)

Wancho can become a base script for indigenous NE languages, says creator

Imkong Walling

Dimapur | November 4

The Roman or Latin script, the script in which English is written, for all its worth has its limits when it comes to capturing the unique tonal variations of indigenous languages. Overcoming the ‘tonal’ barrier sent one man on a quest to studying linguistics and creating an all new script that has potential to become a writing base for most of the indigenous languages in the northeastern region of India and even farther east.

Banwang Losu of Arunachal Pradesh — the developer of the Wancho (Naga) script— was in Nagaland, at the ‘Listener Nagaland Sessions,’ a series of workshops/lectures witnessed on day-2 (November 2) of the 3-day ‘the Listener Nagaland: A Festival of Orality,’ which concluded at the Tetso College on November 4. The event was organised by the IMASI Foundation, Media Management Group for Literacy and Development and INTACH Nagaland Chapter in collaboration with the national Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Government of Nagaland. The sessions centred on strengthening and capacity building of the “multiple stakeholders and custodians for the safeguarding, identification, documentation and inventorying of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) of India.” Losu’s session focused on preserving and promoting indigenous languages and thereby, their culture and identity; and his story of how the Wancho script came about.

According to him, the Wancho language, a tonal language like many other indigenous languages without a script, cannot be effectively expressed in the Devanagari and Roman scripts. Bridging the ‘tonal’ gap motivated him to learn and develop an entirely new script taking inspiration from nature, Wancho cultural symbols and practices, gestures and so on. He maintained that the script, containing 44 letters (15 vowels and 29 consonants), is in no way a plagiarised version of existing scripts and has its own distinct symbols or letters.

He said that he often get asked why the Wancho script has 44 letters. He maintained that the letters came about not as per his fancy; rather it stands for the distinct tones that exist in the Wancho language. His quest started in 2001 and it was 11 years before he completed the script in 2012. The Wancho language classes started in 2016 and in February 2019, the first Wancho language primer book was launched.

Today, some 5000-6000 children can read and write in Wancho and the script has even become an internet language i.e. smartphones and computers can ‘read’ it. There also is an app for ‘beginners.’

Losu, who also runs an NGO— Wancho Literacy Mission and a Wancho language school, however admitted that there are not enough teachers and is struggling to pay the 20 teachers in the school.

“Language gives you value. That value is in your mother tongue. Every language has equal value. We should not lose any language of the world,” he said and called for using information technology to document and preserve languages, especially those without indigenous scripts.

He envisions a world where machine or AI-enabled text to text, text to speech, speech to speech translation of indigenous languages become a reality. He imagines a scenario where a Chakhesang and Sema texts/converses in their parent tongues with technology serving as the in-between translation medium. “We need to focus on this kind of technology for the future. It will help in preserving mother tongue. How good it would be if one can appear interviews in one's own language?” he wondered.

The stimulus

The year was 2001. Losu, around 20-21 years old at the time, was working on a “socio-economic” study of his community. It involved collecting data in English and translating into his native Wancho, when it struck him that Roman was not a suitable script. “I realised that English is not capable of capturing the tonal nuances. Slight changes in tone means meaning also changes,” he told The Morung Express on the sideline of the Listener ICH workshops. “That was the turning point for me to research the phonetics of the Wancho language,” he added.

He started with hardly any knowledge of linguistics but eventually signed up for a post-graduate course in Linguistics at the Deccan College, Pune. The research was tough but convincing people in the initial years was just as challenging, he recalled.

He had received primary education at his native village, Kamhua Noknu in Longding district, Arunachal Pradesh. He went on to complete higher secondary from Miao in Changlang district and later completing his bachelors from the Dera Natung Government College, Itanagar.

Before signing up for the Linguistics course, he got acquainted with a Professor of Linguistics in 2012 at the La Trobe University, Australia— Stephen Morey, whose sphere of work covers “smaller often endangered languages, spoken on the India-Myanmar border.” Morey’s, who linked up with the workshop via video call, research in NE India covered Wancho as well.

According to Losu, the Wancho script can serve as a base writing system for the many Naga and “most of the Northeast languages (that are tonal in nature).”