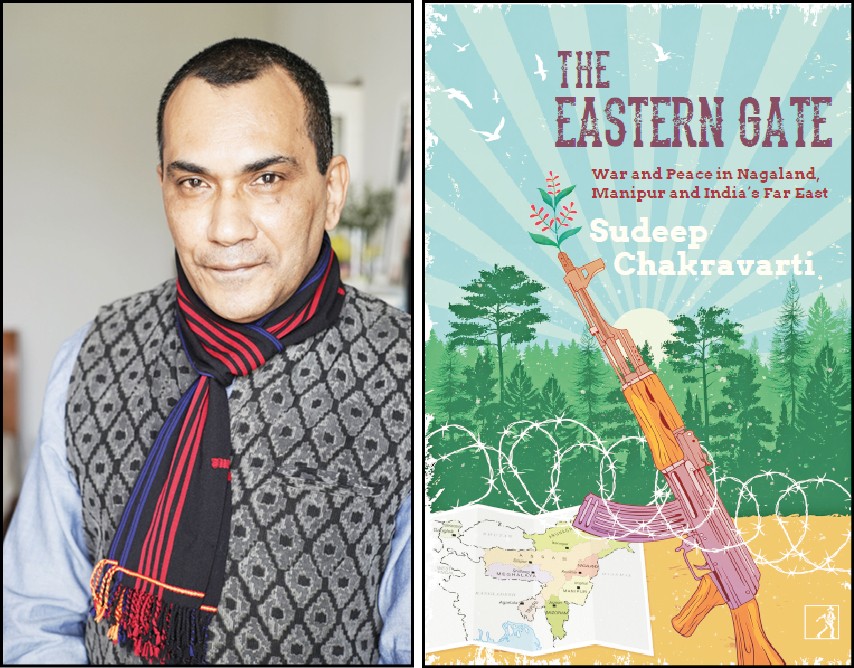

Sudeep Chakravarti

Vishü Rita Krocha

Kohima | May 20

Deeply fascinated by the stunning variety and complexity of the Northeast region, Award-winning author of several best-selling works of history, ethnography, politics and conflict resolution, Sudeep Chakravarti has time and again, traveled to the Northeast,which he prefers to call ‘India’s Far East’.

A keen observer and frequent chronicler of the region, he has offered exclusive insights into the conflict-ridden state of Nagaland and other conflicts for several years. Even having travelled to several conflict hotspots in the region, he confesses that he has never once felt unsafe. To put it in his words—“Whenever I see the Naga Hills draped in their sarong of mist, it takes my breath away. How can I be apprehensive of the very place I fell in love with from the time I first set my eyes upon it?”

In an exclusive interview with The Morung Express, he talks about his latest book- “The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India’s Far East”, which ‘provides a definitive guide to the transition from war to peace, even as he keeps a firm gaze on the future.’

Chakravarti also insists that “the central government absolutely must remove physical, psychological and emotional harassment imposed by legislations such as the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.”

“I wish that “Northeastern sisters and brothers would also demand greater accountability from their political and bureaucratic leaders, and rebel leaders”, he articulates while maintaining that “solutions are never about one party or one person, but about recognizing that others have a legitimate point of view.”

“Those who acknowledge this and are willing to discuss this with dignity and honour will find solutions. Those who choose to continue imposing their will and strong-arm tactics and social media-friendly populism, whether it’s the state or a political party or a rebel group, will continue to perpetuate alienation and conflict and corruption. They will continue to steal the futures of their children,” he says.

MEx: The Eastern Gate- How did it happen? Can you briefly take our readers through the journey of writing this book?

Sudeep Chakravarti: The Eastern Gate has been on my mind since 2013-14. I wanted to follow up the peoples’ stories, histories, narratives in my earlier book, Highway 39, with a more policy-oriented book that also described the history and mechanics of conflict and conflict resolution. I was convinced of it, and wrote about it in columns and essays, spoke about it at lectures and seminars. Because, to expect to ‘look’ or ‘act’ East by overlooking the Northeast is a fool’s errand. This gateway region bordering five countries is a geopolitical sweet-spot, a biodiversity hotspot, a cradle of a thousand cultures, the source of rivers that feeds hundreds of millions, and a crucible of climate-change. What happens here in the next fifty years will decide the course of the Subcontinent for several hundred years.

I outlined my thoughts on two key occasions over 2013 and 2014. The first was at St Joseph’s College, Jakhama, to which Father Abraham Lotha and his colleague Dihe Mao had invited me to present a talk on what was then called the Look East Policy. I expanded the idea with more detail and a regional blueprint when I delivered the inaugural Sarat Mahanta Memorial Lecture in Guwahati in 2014.

The title came to me during one of my visits to Manipur. It was 2017. I was sitting in my room in Imphal, making notes and collecting my thoughts. I had just returned from Moreh, a gateway town. I was in a gateway capital of a gateway state. And right then I recalled a saying of a Meitei activist and respected elder, Ima (or Mother) Mangol, duringan interaction in 2009-10. She had spoken of how, if India were not careful or respectful, the Eastern Gate might shut. And I knew I had the perfect name for the book.

MEx: What kind of research went into it?

Sudeep Chakravarti: Intense travel in Nagaland, Manipur and other states of far-eastern India (I dislike the term ‘Northeast’, which is both incorrect and now has racist and pejorative connotations)to meet people across every spectrum of policy-making and conflict resolution. Various Naga rebel groups, various ethnic and political groups, politicians, bureaucrats, policy makers, security folks, spooks, arms dealers and drug sellers—you name it. I met representatives of every significant ethnic group in Manipur. I met people in other far-eastern states, in New Delhi. I travelled across the region several times. I have personally driven from Imphal to Kohima through every kind of weather, driven from Imphal to Moreh and back, driven around Imphal Valley, and driven from Imphal to Kamjong in the southern Tangkhul homelands! I can still see the rhododendron, see and smell the mist, see the Assam Rifles trucks that I had to squeeze past.

Besides my active field research, interviews, records and field notes, it was also necessary to source relevant documents and books—some rare, some forgotten. For instance, many Nagas haven’t read either the NNC Yehzabo or the modified and more controlling NSCN (I-M) Yehzabo. I have sourced and quoted both in the book. Many Indians forget just how much of a pro-government propagandist the celebrated anthropologist Verrier Elwin was, in the context of Nagaland and NEFA (present-day Arunachal Pradesh). I have shown that using Elwin’s own work. And so on. You can say The Eastern Gate took nearly nine years from conception to research to writing to publication.

MEx: How challenging was it to get interviews with a wide range of people including ‘rebel leaders, politicians, bureaucrats, policy makers, security specialists and operatives, gunrunners, ‘narcos’, peace negotiators and community leaders’ for the book?

Sudeep Chakravarti: All this is always challenging. But I had an advantage. Many had read and heard of my earlier book, Highway 39. Quite a few people in the region had read my other books, my writing in media, had heard my talks.

So, they knew that I speak plainly, speak and write my mind without fear or favour, and have no agenda beyond a transparent purpose to tell stories that need to be told, to offer a narrative devoid of nationalistic arrogance and tell it like it is. These ladies and gentlemen spread the word.

When I was in an area where I didn’t know anyone, or I was to meet someone I hadn’t met before, then my angels—I can’t think of them in any other way—in Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, Tripura and elsewhere helped to open those doors.

Some made calls. Others travelled with me. Everywhere I was given such help. I could not have written Highway 39 or The Eastern Gate without immense help from the powerful, the seemingly powerful, and all manner of people in between. Such help enabled me to understand the hearts and minds of people in Nagaland, Manipur and other regions of far-eastern India.

I continue to learn more in order to write, speak and share more. I have formed deep friendships across several spectrums, even as powerful people and groups are sometimes upset with me for not peddling their propaganda.

MEx: “—and wishful thought for a headline that I dearly love to see for Nagaland, Manipur, and all of far-eastern India: Peace Breaks Out.” What do you really hope would come out of this book?

Sudeep Chakravarti: With The Eastern Gate and with all my books I hope, and seek, the outcome that people learn more about each other’s histories and aspirations, understand why people get angry and what can cool things down with purpose, dignity and honour. I wish to tell people in ‘Mainland India’ that our sisters and brothers in far-eastern India cannot be seen through the prism of New Delhi and Mainland India, that they have their own specific histories, pride, cultures, identities, needs, and aspirations. Equally, that people of ‘Northeast India’ spend more time learning about each other, respecting each other and working collectively to a future of shared peace and prosperity. The alternative is doom.

So, I hope The Eastern Gate is seen as highlighting these histories and aspirations, and as exposing the lies, chicanery, thieving and bullying both by New Delhi and the northeast’s own leaders, both government and rebel, that prevent this future of shared peace and prosperity. Peace has to break out. I dream of it, yearn for it: bishi mon ase deh.

MEx: People are generally still apprehensive of traveling to Nagaland and the North East or the “Far-Eastern India” as you prefer to call it, primarily because of its history of conflict. But given that you have extensively travelled to this region, what are your comments in this regard?

Sudeep Chakravarti: In all my years of travelling in this region, even to several conflict hotspots, I have never once felt unsafe. Perhaps it is on account of my journalistic training. But I like to think there’s more to it. Fear and animosity beget fear and animosity. Respect and honesty of purpose begets respect and honesty of response. Homes and offices and hearts and minds have been opened to me. People have shared their food with me. I have formed deep bonds across the region. I consider Northeast India my spiritual, emotion and even culinary home. I put on a couple of kilos each time I visit anywhere in Northeast India from all the excellent food and beverage. Besides, I have learned to make several varieties of Naga chutney (I have a Naga bamboo mortar-and-pestle). I have learnt to cook Naga pork (usually in the Ao and Lotha ways although my friends from other tribes say I could do much better with their recipes!) and Khasi-style pork. There is usually axone, raja mirchi, and fresh or dried bamboo shoot in my home. I extol the virtues of black sticky rice to anyone who cares to listen. Whenever I see the Naga Hills draped in their sarong of mist, it takes my breath away. How can I be apprehensive of the very place I fell in love with from the time I first set my eyes upon it?

MEx: You are a frequent chronicler of the North East. What is it that one thing that fascinates you so much about the region?

Sudeep Chakravarti: The region’s stunning variety and complexity.

MEx: Any final thoughts?

Sudeep Chakravarti: I wish North eastern sisters and brothers would also demand greater accountability from their political and bureaucratic leaders, and rebel leaders.

Solutions are never about one party or one person, but about recognizing that others have a legitimate point of view.

Those who acknowledge this and are willing to discuss this with dignity and honour will find solutions. Those who choose to continue imposing their will and strong-arm tactics and social media-friendly populism, whether it’s the state or a political party or a rebel group, will continue to perpetuate alienation and conflict and corruption. They will continue to steal the futures of their children.

The central government absolutely must remove physical, psychological and emotional harassment imposed by legislations such as the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act. Moreover, leaders and people of Northeast India should not always look to New Delhi for solutions, but look to each other. Instead of flying to Delhi at the drop of a greedy hat, try flying to Dimapur, Imphal, Guwahati, Gangtok, Shillong, Agartala, Aizawl. See the future as a collective. See the big picture. It’s possible to do so without sacrificing identities, cultures and aspirations. Let there be a greed for peace and prosperity, not greed for perpetuating ethnic and religious hatreds and political one-upmanship.