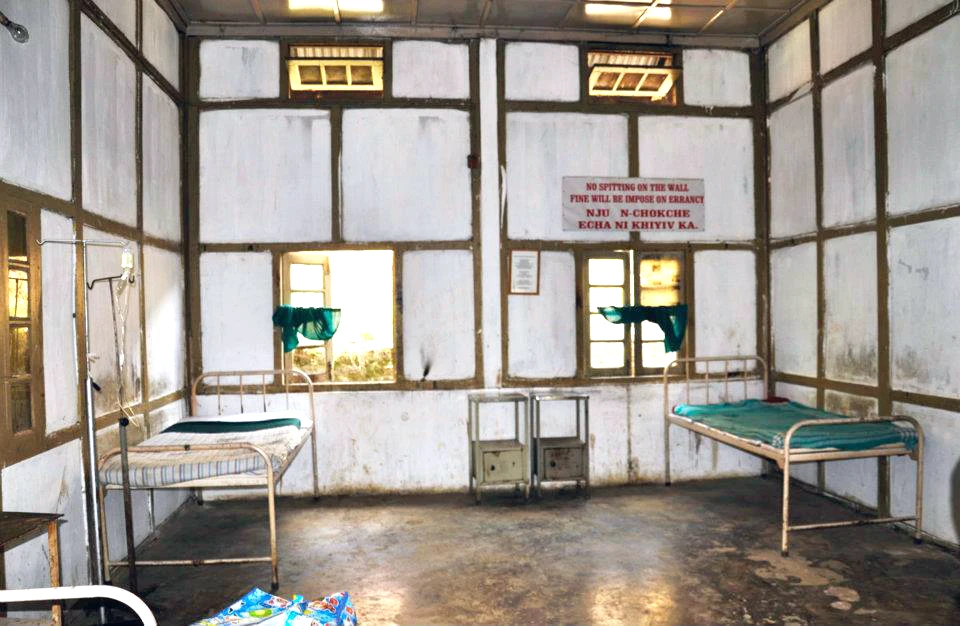

Can the coming Assembly Election in Nagaland change this? Entrance to the Wokha district hospital awaits patients with a broken down truck. (Photo courtesy wokhawokha)

Aheli Moitra & Bensile Tep

Wokha | February 10

Despite every promise, village folk in Nagaland continue to struggle for better and easier access to health care and services.

Road condition across the state, especially to peripheries, has contributed to the inaccessibility of primary health care. Worse, there is lack of sanitation, clean drinking water supply, and women’s health issues. “Road connectivity within Wokha district is so bad that people have trouble accessing the only district civil hospital. They are poor and some cannot even go to Kohima or Dimapur for better treatment, forget about outside the State,” highlights a doctor posted at the Wokha District Civil Hospital. This has also contributed, not solely, to infant mortality, wherein expecting mothers from peripheries take a ‘bumpy’ ride to the district hospital.

In Wokha, there are adequate Primary Health Centres, Sub-Centres, and Community Health Centres; however their downfall is the lack of staff. There are a number of culprits here. Bad roads give rise to poor standards of living in the inner reaches of the district where doctors refuse to go when posted. “Even the government quarters here are left for us to repair,” says a doctor who has been posted in various places in the State. In his current place of posting, he had to have the government quarters repaired at his own expense. The situation is worse in inner constituencies.

Bureaucracy plays along. The recent re-shuffling of medical professionals created a furore, owing to its lack of logic among other things, in the machinery and management of the Directorate of Health and Family Welfare. In Wokha, the reshuffle left the district hospital with two surgeons, one gynaecologist, and no anaesthetist. In another health Centre, a pathologist was transferred to be replaced with an anaesthetist. In a Centre in Longleng, there is an anaesthetist but no gynaecologist.

The reshuffle, now in abeyance, was either motivated or blind.

“The Government should contextualise the placement of doctors and other medical staff. Managers should be exposed to the grassroots and policies should be made based on this experience,” reflects another doctor from the Wokha civil hospital. That is a suggestion not easily applied. There have been seniors in the medical department never transferred from Kohima till retirement.

“A woman in peripheral Nagaland remains anaemic, a simple disease of malnutrition, while officers in Kohima are obese. This is a sign of policy failure,” he frets.

For health care availability, the Centre is pumping in adequate money, but the question remains—How much is reaching the locals or benefitting them?

Though central schemes have helped raise the quality of health care across the state in general, and communitisation has kept things slightly on their toes, neither has worked effectively yet. The Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS) under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), for instance, provides at least Rs. 5,00,000 for the upgradation/maintenance/civil works of a hospital per year. “This amount is enough to provide at least one drip, one syringe and one needle to every patient if used like that,” explains a state affiliated doctor. More often, however, when approached for funds, seniors resort to “no funds”.

In Wokha, the DC has personally intervened to monitor fund usage, which has brought in a small level of accountability. As for the community’s role, The Kyong Eloe (Women) Hoho, while on tour of the district’s health care centres, had to get a Centre opened at 9am. A health practitioner pointed out that communitisation cannot work where people are poorly educated, unaware of their rights and the possibility of schemes. If only a percentage of the whole is aware, funds are liable to be misused.

The existence of ‘excess’ health centres in Wokha do not help locals when there is lack of essential drugs and equipment. The staff at Wokha District Hospital, for instance, asked for a small blower in the delivery room, but were sanctioned a fax machine on paper. A government hospital, the local poor’s only access to health care, is now charging its patients for even ambulance fuel.

Such examples help explain why the Nagaland State Government has been running up a bill of Rs. 20 crore a year in reimbursements for those from the State who are forced to seek medical attention from outside the State, as lack of adequate services means people have to go outside the State to seek healthcare.

The Directorate of Health and Family Welfare had listed one of its main goals as to maintain constant supply of essential drugs, and improve the infrastructure of the basic health units. Like others, this has also remained wishful.

Note: No doctors or commentators have been named in order to protect their identity and for their security